Having lost these accounts in the data corruption of a couple years ago, I wanted to get them back on here as I think they were fun (others may find them tedious or inconsequential, lol). They are missing subsequent edits and all of the photos, stuff lost to the ether. I cobbled this composite version together from my notes, those of our game-session scribe, and the recollections of a few players gleaned from a number of phone calls. If I find any other bits or photos, I’ll add them over time.

The Riddle of the Sands

22 April 1915

In 1903, Smith, Elder & Company published a novel written by Erskine Childers, a guy who was born in England but raised by his mother’s family in Ireland following the death of his parents. The book, “The Riddle of the Sands”, is considered a ground-breaking piece of fiction, arguably the first of the espionage genre that would become so popular five decades later following the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the Cold War.

My father, a voracious reader throughout his life, had a copy of RotS in his library, the place where I first encountered it. I’m not one for reading bits of historical fiction more than once, but I recall reading Childers’ book two or three times when I was a kid. Much like the later works of Fleming, Clancy, and others, the story is heavily laden with political, geographical, and technical facts which bear heavily on the story. This, together with the writing style of the late Victorian era, required a few reads to digest everything and make sense of it.

Childers wrote his book at a time when Britain’s Foreign and War Offices were trying to determine who and what was the country’s primary threat as the calendar turned over into the new century. To his credit, Childers identified Germany as Britain’s likeliest adversary and developed his somewhat fantastical story within that premise.

The Frisian Islands are a long band of barrier islands that run along the western Danish and northern German and Dutch coasts. Much like the barrier islands along the Atlantic coast of the United States, the Frisians are ever-shifting bits of sand formed by the tides and currents of the North Sea. Only in populated areas where man has attempted to intervene in the endless ebb of water and sand has there been any stability; otherwise, these islands are relentlessly on the move. For centuries, they have played both havoc and sanctuary for the coastal shipping lanes of northwestern Europe, and their strategic importance lies at the center of Childers’ book.

From the First World War’s start, both the British and German navies found reason to extensively mine this southeastern corner of the North Sea, first as a means of interdicting the flow of goods and materials in and out of Germany’s northwestern ports, and second as protection for the great German naval base on the Jade. Throughout the war, there was an extensive effort by both sides to penetrate, disrupt, and/or defend the integrity of the vast minefields sown here. Minelayers, minesweepers, trawlers, drifters, submarines, and various light units fought a seemingly endless series of actions in these treacherous waters, a cycle that appeared to be nearly as predictable as the tides.

Some historians credit Childers’ book with having influenced Britain’s strategic deployment of its naval assets in the years leading up to the First World War. That seems rather far-fetched to me, but Churchill, for one, was known to have commented on it.

With this as a backdrop, together with the grander strategic notions laid out in Childers’ book, there forms the basis for a series of games to be played over the remaining weeks of this summer of 2021. More than a century after it all went down, there remains only a cursory view of these vicious actions fought in coastal waters, so they will be largely surmised. No matter, the heaviest units of the Grand Fleet and High Seas Fleet shall be restricted to the fleet cabinets, for this shall be the realm of the destroyer and the torpedo boat.

In mid-April, 1915, Admiral von Pohl dispatched 2nd Scouting Group on a mining operation supported by the HSF, and a week later a sweep in the direction of Dogger Bank was ordered with hopes of engaging British units. Concurrent with this operation was a secondary effort to clear British minesweepers and drifters operating around the eastern end of the Frisian Islands.

Action off Ameland

22 April 1915 (part 1)

Von Pohl took command of the High Seas Fleet (HSF) in the first week of February, 1915, relieving von Ingenohl following the debacle at Dogger Bank. There was a price to be paid for the black eye suffered less than two weeks before, and von Ingenohl, a man whose operational view was not too different from his replacement, paid it.

Within months of the start of the war, there developed two prevailing strategic notions within the Imperial Navy high command regarding the employment of the HSF. One advocated for an aggressive campaign directed at the Royal Navy, anytime and anywhere, while the second was far more conservative, prioritizing coastal defense and preservation of naval assets. Von Ingenohl’s thrust-and-parry strategy had ended in failure, primarily due to poor operational execution. Von Pohl largely withdrew from the North Sea, focusing instead on the U-boats and their assault on the shipping lanes surrounding Britain.

For the next twelve months, the HSF would see little action. Operations were conducted primarily in coastal waters, the only exceptions being a token number of sorties less than 150 miles out with the misplaced hope of encountering British sweeps. The Royal Navy, however, had scarce reason to venture south other than to support its interdiction efforts and to observe its rival’s activities. A “phony war” of sorts developed, only ended by von Pohls’ death from liver cancer in January, 1916, and Scheer’s elevation to command.

The Day Before - 21 April 1915

Korvettenkapitän Gerhard von Gaudecker was on the bridge carefully surveying the charts with his executive officer when the change of orders were received early in the afternoon of April 20. SMS Hamburg, a Bremen-class light cruiser, had been sent two days earlier to patrol northwest of Mellum. It was treacherous work, plying the narrow band of open water that intersected the vast mine belt that protected the mouth of the Weser. His patrol area would occasionally take Hamburg within 800-900 yards of the field, leaving a razor-thin margin for navigational error. Only five months earlier, the armored cruiser SMS Yorck had been gutted by a pair of mines when she inadvertently wandered outside a designated channel through the field. Many lives along with a number of naval careers were terminated that day, and Gaudecker desperately wanted to avoid a repeat. Unlike Yorck, he had no pilot aboard, and the weather was poor, with low-lying clouds, occasional fog, and a steady light rain. When new orders came sending him west, Gaudecker was not displeased.

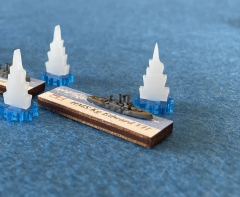

SMS Hamburg.

Hamburg’s new orders would take her west to join four torpedo boats from 2nd Torpedo Boat Flotilla to execute a sweep of the waters north and west of Borkum, the westernmost of the East Frisian Islands some 10-12 miles northwest of the mouth of the Ems. The Germans maintained a sizable military installation on the island, one that had been the subject of a clandestine British operation in 1910. Now, some seven months after the start of the war, a number of drifters and other small craft had been observed in the area, along with reports of suspected Royal Navy minesweepers. Hamburg and the torpedo boats were charged with clearing the general area of enemy operators.

*****

Lieutenant Commander Geoffrey Layton stood peering over Petty Officer Davies’ shoulder, the latter’s hands and arms covered in grease and diesel oil, using an adjustable spanner to gently tap on the broken driveshaft coupling at the back of one of E13’s two Vickers 8-cylinder diesels. With the dim light overhead flickering ominously, there was no longer any fooling themselves. They both knew it was a mechanical failure they had no capability of repairing while rolling about in the middle of the North Sea. They would have to return to Harwich for repairs, if they could.

Despite the sentiments of a number of her crew, Layton refused to believe E13 was a jinxed boat. Following his command of the coastal submarine C23, he’d been assigned to the new E13 at her commissioning in December, 1914, the fifteenth of the E-class submarines that had started rolling down the slipways in late-1912. Admittedly, she had encountered a number of “incidents” during her shakedown and early maneuvers, but now she was on her first war patrol, destined for the western Danish coast. Departing Harwich on April 18, she had made good progress when, approximately 45 nautical miles north of Ameland, diesel No. 2 let go. After 36 hours trying to make repairs, they’d given up and would now turn for home. Barely able to make five knots while pushing against the North Sea swells, half the crew sick, and difficulty recharging the batteries, she was largely a sitting duck for anything that might come along. Layton, his sense of optimism fading, began to rethink his relationship with E13.

Reporting his situation in a coded message to Harwich, Layton was advised that HMS Bonaventure, an old Astraea-class cruiser which had been tasked as a submarine tender, was being dispatched to assist with repairs or, failing that, to take E13 under tow for return to the yard at Dovercourt. Bonaventure’s captain, Commander Stanley Willis, estimated he could be on E13’s position in less than a day’s sailing. Until then, Layton and his submarine were directed to continue inching their way westward.

To escort Bonaventure in her efforts to reach E13, a small scratch force from 4th Destroyer Flotilla was assembled, consisting of leader HMS Swift and destroyers Acasta, Christopher, and Owl. Captain Charles J. Wintour, overall commander of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, would personally lead the destroyers. Wintour’s 4th DF, which typically operated in conjunction with Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force and the Dover Patrol, found itself temporarily short-handed, as most of the DDs were having to maintain patrols of the Thames Estuary and coastal waters as far south as eastern end of the Channel. Wintour, with his four destroyers, expected an out-and-back of no more than 72 hours.

*****

Bert “Duffy” Landon’s trawler, motoring northeast at ten knots, was pretty far south of the traditional fishing grounds off Dogger Bank. Overnight they had passed a scant 10 miles from the Dutch coast, at one point close enough to have seen the light at Zandvoort. With the hold empty of fish, the booms drawn, and the nets stowed, they showed little pretense to be where they were.

Primrose had been Landon’s boat for more than a decade, acquired from an old Cromer fisherman who’d retired not long after the millennial calendar turned over. Prior to that, Landon had briefly worked in the pits, something he’d despised despite his family’s long history with mining. No, he’d left the mines, instead working as a fishing hand for seven or eight years, saved his money, and when the trawler came up he’d made arrangements with the owner to buy it on time. Crab and lobster in the summer, herring in the fall, then cod through winter, it was a never-ending rotation of long hours and hard, dangerous work. Still, he never once considered returning to the pits.

Trawler Primrose.

If it wasn’t already difficult enough, the war had raised the bar even further. A couple of the boats operating from Cromer had inexplicably gone missing; one day they went out and simply never returned. No trace was ever found – no wreckage, no debris, no bodies, nothing, they just vanished. Now the drifters had taken to operating in pairs or small groups, and within a few weeks the new dangers of the trade became apparent.

In November, a pair of Cromer’s trawlers were surprised by a surfaced German submarine. Ordered to stop and abandon their boats, one captain did so, the other dropped his lines and managed to slip away. Upon returning some thirty-six hours later, the captain of the escaped boat reported the incident to local authorities and subsequently to Royal Navy personnel. No trace of the other drifter or her crew was ever found.

Two weeks later, a trawler dragging for herring unknowingly snagged a naval mine in her nets and was destroyed while winching her catch alongside. One badly-injured survivor was picked up by a nearby fishing boat, the man able to detail the circumstances of the incident. A second drifting mine was observed a few days later by another boat, this successfully detonated from a safe distance by rifle fire. The danger was escalating rapidly.

By January, 1915, 45 boats had been lost or disappeared and the fishing fleet was in an uproar. There were reports of submarines and torpedo boats sweeping the fishing grounds and, true or not, of crews being machine-gunned in the water following the sinking of their boats. Calls for protection by the Navy were dismissed as impractical, but offers were made to arm trawlers for their own defense. Landon, for one, jumped at the opportunity. In early February, he and his six-man crew took possession of a 20 year-old short-barreled Hotchkiss 3-pounder which they mounted near Primrose’s bow (positioning and deck modifications as directed by the RN team that delivered it). A few days later they received 90 minutes of training on the gun’s use, along with two crates containing 40 shells. Landon supplemented his armament with a pair of Lee-Metford .303 rifles that he stored in the wheel-house.

Primrose made a pair of short fishing runs in late February and early March, both of which were uneventful. On their third outing, a 96-hour run south and east of the Norfolk coast, they encountered nothing unusual other than an overturned, partially submerged steel buoy which they initially thought might have been a drifting mine. Three shots from the Hotchkiss (two misses and one hit) dispatched the buoy, an object that posed a considerable threat to any small vessel that might come upon it.

After a relatively quiet March, the number of boats lost started to rise again. With the risk of mines, submarines, and torpedo boats increasing, a number of trawlers were being requisitioned for minesweeping and patrol duties, a fate Landon hoped to dodge. The cod, however, were running in small numbers, and doing some paid work for the navy began to look lucrative. An early-April meeting produced a request for Primrose to temporarily move south where an increasing number of drifters and fishing boats were working. Landon’s assignment was a reconnaissance of sorts, a slow meandering cruise up the Dutch coast to observe and document the extent to which the German Navy was expanding its reach into the southern end of the North Sea. Couched as a one-off, and in light of everything going on, Landon and his seven-man crew agreed to undertake the request.

Primrose departed Cromer early in the morning of April 19, 1915, slipping past the breakwater at 0340. Preparations were minimal, laying in a couple weeks’ worth of provisions while offloading or stowing most of the fishing gear. A ring of sandbags now encircled the shield-less Hotchkiss, a stiff canvas tarp tied over it.

The voyage south was uneventful. Landon set a three man watch, rotating every six hours. They made the 100-mile trip south to Harwich in twelve hours. There they received charts and maps of the Dutch and German coast, including the position of known facilities and minefields. A new three-kilowatt radio was installed, along with the protocols for its use, and they were given a Danish flag to be flown if challenged. The radio and all charts, maps, and papers were to be destroyed if confronted. At 1930, having topped off the bunker with diesel oil, they slipped their mooring and headed down-channel at a leisurely eight knots. Twelve miles out, the coast disappearing behind them, they doused the lights and set their course due east, raising their speed to ten knots. A days sail and they’d be on the Dutch coast.

*****

Von Gaudecker and cruiser Hamburg met the four torpedo boats at dawn on April 21, five nautical miles southwest of Juist near the mouth of the Ems River. He brought the torpedo boat commanders aboard to both meet them and to strategize on how best to execute their sweep of the waters north and west of Borkum. His inclination was to divide them in an attempt to cover as much of the assigned sweep area as possible, but he had concerns about maintaining control of the operation. He instead directed that they would execute a broad sweep of the area in a wide, quarter-line formation, with the TBs slightly ahead and no more than 5000 yards apart. Given good weather, this would yield a search pattern some 18 miles wide. Hamburg and her TB charges would proceed west along the north shore of the Frisian Islands some 80 miles to a point past Terschelling, then a turn north-northeast into a broad arc that would eventually reach Heligoland. There they would run south to return to base, threading their way through the mine belt laid across the mouth of the Jade.

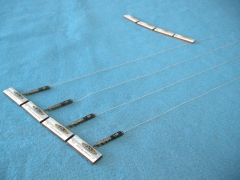

The torpedo boats, S141, S142, S143, and S144, were all of the S138-class, commissioned in 1907. They were an older type and relatively lightly armed, recently refitted with a pair of 88mm SK (quick-firing) L/35 cannon, a single 50mm SK L/40 cannon, and three 18-inch torpedo tubes arranged in single-mounts. They were quick, but not as fast as one might expect, topping out at around 31 knots.

Torpedo boat S141.

If the torpedo boats were old, Hamburg may have seemed geriatric. Launched in 1902 and commissioned in 1904, she was armed with ten quick-firing 4.1-inch, supplemented with ten 1.5-inch Maxim for close-in defense. She also had a pair of 18-inch torpedo tubes in reloadable submerged broadside mounts. Flank speed was 22 knots. Hamburg, assigned to 4th Scouting Group, had participated in December’s raid on Scarborough where she’d had a brief encounter with British destroyers. Otherwise, her war had been relatively quiet.

The run west was largely uneventful, encountering only a few Dutch scows and the German coastal steamer Tümmler churning past, her holds piled high with a load of coal. At 1530, having pushed nearly 20 miles west of Terschelling, Gaudecker ordered the turn north, continuing at a leisurely 14 knots. Twenty minutes later they encountered what appeared to be a large trawler sailing across their bows heading southwest. Gaudecker sent S141 to investigate, soon reporting it as the French armed trawler Faucon. Apparently surprised by the German torpedo boat’s rapid approach, a shot across the bow and the Frenchman stopped. After a brief boarding and inspection, the crew was ordered into a pair of dinghies and Faucon was dispatched with three or four rounds from the torpedo boat’s 88mm.

In just over ninety minutes, S141 was back in its position on the point. At 1806, S143 reported a fisherman some seven or eight miles ahead on a northwest heading. Gaudecker again ordered S141 off for a look, and the TB was soon charging off at 30 knots to run down its quarry.

*****

The weather overnight had been good, almost too good for Landon’s liking. The sky was crystal clear, and a high half-moon reflected off the sea ahead. Good visibility, yet around midnight Primrose was nearly run down by an unknown steamer heading south along the coast at what Landon estimated to be 25 knots. Running without lights in the dark was a huge risk, no doubt, and he and the crew were left badly shaken by the near-miss. How his first mate MacGregor, on watch at the time, had missed the onrushing behemoth was a mystery. Sunrise, with its own associated risks, couldn’t come soon enough.

By 1030, they were past Texel and headed out into the open sea. Landon watched the Frisian Islands and the Dutch coast melt away astern, glad to be clear of the constrictions he felt when operating close to shore. Consulting the charts, he set a course that continued north-northeast, figuring he’d pass the last checkpoint and turn for home by 1800. A long 200-mile run west would have them back in Cromer by evening the next day.

Primrose continued on her northeastward heading throughout the day, uninterrupted by not so much as a glimpse of another craft. The calm sea was eerily empty, horizon-to-horizon, and Landon began to suspect the entire excursion to have been a great waste of time. Midafternoon, he turned the trawler a few degrees further north, continuing at a steady ten knots.

At 1818, one of the men yelled that a craft was approaching from the port quarter. Through glasses, Landon couldn’t quite discern who or what it might be, but the tall bow wave indicated it was coming fast. Large, dark, and low to the water, he figured it was likely some sort of German patrol craft.

With the Danish ensign fluttering from the fantail, gear stowed, and the Hotchkiss hidden under the heavy tarp, he wondered how long the charade might last. Suspecting not long, he figured he would have three choices - continue pretending to be a neutral and act dumb, immediately stop and surrender, or fight it out. All three seemed likely to get them killed, some sooner than later. Leaving the wheelhouse unattended, he ran forward to tell MacGregor to get the men ready to use the 3-pounder. While the Scotsman began untying the tarp, Landon returned to the wheelhouse. He pulled out the two rifles, handing one to a deckhand along with a cartridge box. The other he kept for himself.

The German torpedo boat gradually reduced its speed as it approached, closing to within a few hundred yards to casually look over the trawler. While the fisherman appeared rather nondescript, Second-Lieutenant Wilhelm Keil had his suspicions this wasn’t just a Danish fishing boat. Why would one of their boats be so far south and west of the Danish coast? It wasn’t impossible, but it wasn’t likely either. Keil told his XO to have the trawler stopped for boarding and inspection.

Flashes from a lamp meant nothing to Landon, nor would he have heeded them had he known what was being signaled. He could see a sudden milling about mid-ship, along with a few crewmen manning a rather ominous-looking gun forward of the main-mast and the conning tower. Feeling a mixture of anger and adrenalin welling up inside him, he maintained his course, raised speed slightly, all the while keeping an eye on the dark-gray silhouette gliding along off to his starboard.

Minutes later he heard a loud crump, a shot fired by the torpedo boat, throwing up a great geyser of seawater a 100 yards or so ahead of Primrose’s port bow. There could be no misunderstanding this message, Landon thought to himself. Never one to shrink from a fight, no matter the odds, he eased his speed ahead another knot, then waved his arm at MacGregor who, with a great heave, pulled the tarp off the Hotchkiss and, together with another crewman, scrambled over the sandbags.

Praying to God he’d hit something, the Hotchkiss recoiled as MacGregor sent his first shot toward the German torpedo boat. The lack of training did not serve them well as, even at such short range, the round sailed over the TB’s aft funnel by some 30 feet. This served to get the attention of the German gunners who, within less than a minute, began returning fire.

Landon looked at his watch, surprised it was 1842, only 20-odd minutes since they’d first seen the German’s approach. MacGregor fired again, this round also sailing far wide of the target. The TB’s forward gun barked, missing short by some 75 yards, sending seawater raining down on the trawler. Landon spun the wheel to starboard, hoping to turn into his antagonist’s line of fire while presenting his narrowest profile as a target.

MacGregor continued firing but was unable to put a round on the TB. The Germans, however, seemed to be gradually getting the range. An 88mm round slammed into the water just a few yards off the port side, steel splinters tearing into Primrose’s wooden hull. Keil ordered S141 to increase her speed, trying to get around on the trawler, but Landon kept turning inside him, so he decided to straighten up and move away, then make a run back in.

On his first pass, Keil’s TB put a round into Primrose’s forward hold, blowing a large hole in her hull just above the waterline. As S141 passed, the aft 88mm landed another round, this burrowing into the sandbag ring around the Hotchkiss, crushing the mount and disabling the gun. The blast threw MacGregor nearly twenty feet, pinning him against the port-side gunwale under a steel hatch cover. The crewman who’d acted as the Hotchkiss’ loader was dead. Another crewman scrambled over to get MacGregor out from under the heavy cover while Landon, his knee braced on the wheel and the rifle laid across the ledge of the wheelhouse window, pumped .303 rounds into the torpedo boat as it hurtled past.

On the TB’s next pass, Primrose took another hit, this at the waterline on the starboard side where she began slowly flooding. Twelve minutes later, another hit on the opposite side, showering the trawler in seawater and splinters. The shell had penetrated to the engine compartment where the marine diesel, immersed in rising seawater, spluttered to a stop. Slipping down a ladder, Landon was greeted by a sight of total carnage; in places he could see sunlight through parts of the hull. Smith, his engineer, was nowhere to be found. With water nearly to his chest, he climbed back up the ladder to the clatter of machinegun fire.

As the deck began to pitch sharply to starboard, the mast and derrick came crashing down, nearly crushing the wheelhouse. His youngest deckhand, a 15 year-old boy from Metton, remained crouched on the stern, blazing away with the other rifle. Landon yelled to him to go over the side, telling the same to another crewman who helped MacGregor get clear of the sinking trawler. Landon smashed the radio with the butt of his rifle, then threw the maps and logbook into a steel box on the deck. He calmly shot a hole in the box, tucked it under his arm, then tossed the rifle and himself over the port side. Once in the water, he held the steel box under him, feeling it fill with water and sink out of his grasp. He looked up to see the 15 year-old swimming toward him, then together they swam off through the debris and diesel oil, to find MacGregor and the other man. Primrose, his beloved trawler, rolled over and sank behind them.

It was dark when S141 rejoined Hamburg and the other torpedo boats. The action with the trawler and subsequent recovery of the survivors had consumed nearly three hours and expended more than 40 of their 200 88mm shells. Landon, who’d felt certain they’d be shot before or after they were fished from the sea, found himself drinking coffee in the torpedo boat’s wardroom. MacGregor, his left leg badly lacerated and his left arm broken in two places, was being tended to by a couple of German crewmen. The other two men had been taken below for dry clothes. The loss of the others weighed on him, especially when S141’s young second lieutenant commander gave them the news that they would likely spend the rest of the war in a prisoner camp once S141 returned to Germany.

His boat gone, a third of his crew dead or missing, and facing an uncertain time ahead, it could have been easy to feel sorry for himself. Then again, four of the seven of them were still alive; it seemed likely that things could have turned out worse, much worse.

Tomorrow would prove him right.

Action off Ameland

22 April 1915 (part 2)

Day of Battle

With E13 in tow, Wintour directed Willis and Bonaventure to set course on a west-southwest heading, aiming to take the shortest route back to Harwich. An alternative would have been to head due west, approaching the sanctuary of the English coast and its patrol regimen overnight. There, in relative safety, they could turn south to reach the Thames Estuary. This, however, would add upwards of ten hours to the return voyage and risk entanglement with German fleet units engaged in an operation to their northwest (Wintour had received wireless reports in the early hours of the 22nd of enemy operations northeast of Dogger Bank).

Wintour split his escort, with HMS Christopher and HMS Owl taking up a position approximately 3000 yards off Bonaventure’s starboard bow, while HMS Swift, his flag, and HMS Acasta stood some 4000 yards off the old cruiser’s port quarter. The crews suffered some discomfort as the destroyers rolled in the gentle swells while trying to maintain their positions at this dreadfully slow speed. No matter, they’d be home soon enough. Wintour ordered the watch doubled and went below to check on repairs to a ventilation problem that had been reported by the galley earlier that morning.

Old RN cruiser HMS Bonaventure.

At 0948, a report of a smudge of smoke on the horizon dead ahead came to Bonaventure’s bridge. It was faint, but there, and after a few minutes they were able to confirm that, whatever “it” was, it was headed directly for them. Commander Stanley Willis ordered his men to their action stations while advising E13 that, depending upon a determination of any threat approaching, the tow would be dropped and that the submarine would be on her own. A quick wireless message was sent to Wintour, advising of the sighting.

Upon his recall to Swift’s bridge, Wintour turned his attention westward toward the oncoming ship(s). They remained unable to discern precisely what approached, but at 1018, a second message soon came in from Bonaventure, reporting that the oncoming target was comprised of one large ship, possibly a light cruiser, trailed by a number of destroyers or torpedo boats. Willis estimated the range was some 19000 yards and that the presumed enemy force was closing at an estimated speed of 17 knots. Wintour ordered Willis to drop his tow and raise his speed to 12 knots. He then ordered the destroyers to ascertain and engage the target at flank speed.

*****

Korvettenkapitän Gerhard von Gaudecker watched the torpedo boats gradually form into a column astern of Hamburg, a maneuver largely completed by 1000. On their current east-northeast heading, the cruiser, churning along at 15 knots, was headed straight into the morning sun, hampering his ability to see dead ahead. It did not, however, present a problem for the men in the forward director position, reporting smoke ahead and off both their starboard and port bows. Within minutes, Gaudecker radioed Keil in S141 to raise speed to 20 knots and to maintain the line astern.

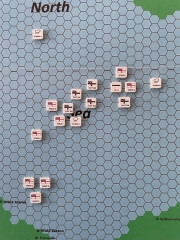

It wasn’t long before Gaudecker had reports from his XO that the force ahead comprised a light cruiser escorted by two pairs of destroyers, one pair on each side. By 1048, the range between Hamburg and Bonaventure was down to 11000 yards, with Wintour’s destroyers less than 10000 yards out and closing fast. He had to make a decision quickly, the two forces running in on each other at a combined speed of some 50 knots. To turn south in a running battle risked getting himself quickly pinned against one or more of the mine belts. No, he would turn north-northeast to gain position and bring his torpedo boats to bear. At 1054, the Germans began making their turn north.

At 1100, the umpire declared the first random event of the day, a ship striking a drifting mine. A series of die rolls reveals S141 as the unlucky ship. With the turn northeast underway, Gaudecker hears a tremendous blast astern. He turns to see S141 shrouded by a curtain of smoke, steam, and seawater, pitched to starboard some 30 degrees. Her back broken, the torpedo boat’s stern drifts in a slow spin to port, her forward section sinking rapidly. S142, immediately astern of the stricken torpedo boat, veers sharply out of line, narrowly avoiding collision with the aft section of S141. Second-Lieutenant Keil, his crew, the survivors of Primrose, along with his ship are lost.

Hamburg barrels ahead, but the TBs, having had to turn out of line to avoid the wreckage of S141, are now some 700 yards astern on the cruiser’s port quarter. Gaudecker orders Hamburg to open on HMS Christopher, now a scant 2800 yards off the cruiser’s starboard bow. At 1106, a German 4.1-inch round penetrates Christopher’s forward boiler room. The resulting carnage sharply reduces her steam, dropping her speed nearly in half with the partial loss of power.

As the ships close to near point-blank range, the combination of headings, tube positions, and blocked line-of-sight temporarily prevents anyone from acquiring a firing solution for a torpedo attack. HMS Owl slashes past Hamburg, scarcely 500 yards astern of the cruiser. Owl’s 4-inch scores a single hit, disabling one of Hamburg’s stern 4.1-inch mounts. Hamburg batters the destroyer in turn, scoring two engineering hits that knocks out all power. Gunfire from the torpedo boats is ineffective.

With both DDs from his northern flank temporarily out of action, Wintour begins a charge from the south. Bonaventure, creeping along in the center of the table at a leisurely 12 knots, now opens on Hamburg at a range of 7300 yards, missing with her forward 6-inch. Gaudecker and Hamburg, who’d not been paying much attention to the old cruiser, returned fire, his salvo landing well short of the target. Wintour orders Swift to open on the torpedo boats, the range being just 4100 yards. A single 4-inch hit in her engineering section drops S144’s maximum speed to 19 knots, just a knot less than her current speed.

HMS Swift

The battle has now taken on this great clockwise rotation, with the Germans being at the Noon position, Bonaventure at the four o’clock position, and Wintour with Swift and Acasta at the seven o’clock position. Wintour maintains his speed at 29 knots while trying to turn inside Gaudecker’s arc toward Bonaventure and Willis, who is now turning toward Hamburg as well. Lieutenant-Commander Robert Hamond, HMS Owl’s skipper, manages to get her forward boiler room back online by 1130, and she, together with the wounded HMS Christopher, turn east to resume their pursuit of the German torpedo boats.

HMS Swift is rapidly reeling in the German force. At 1136, she lands a hit on S142, stoving in bulkhead A7 just ahead of her forward engine room. The torpedo boat begins flooding, but is able to maintain her speed and position as damage-control crews try to repair the damage. The torpedo boats return fire with their 88mms, but score no hits. Six minutes later, S142 fires a spread of torpedoes at the oncoming Bonaventure, but all fish pass safely ahead of the cruiser without any evasive action. S144 takes a hit at the waterline from Swift, resulting in one hull-box of damage.

A steady exchange of fire continues with few hits. Swift manages a 4-inch hit on Hamburg that takes down her foremast along with her searchlights and disables the wireless room. S142 gets her flooding under control and S144 restores full power. At this point, Gaudecker decides to break off the action, knowing he can outrun Bonaventure and deems it unlikely that Swift and Acasta will continue their pursuit. He orders all ahead flank.

Of course, the wildcard in all of this is E13. After being cast off by Bonaventure, Lieutenant-Commander Layton crept along on the surface at five knots, the action of the morning being some distance to the west. By 1130, however, the battle was observed to be moving back toward them, and he ordered E13 to submerge. With fully charged batteries, he expected he had some ninety minutes to two hours of runtime under water before he’d have to consider resurfacing. As the Noon hour approached, he sees that the Germans were moving in his direction and that he was likely to get at least one chance before they passed.

Layton, however, had misjudged the speed of the onrushing German ships. He ordered E13 hard over and lined up his shot. The oncoming torpedo boats would pass scarcely 500 yards in front of him, and Hamburg not more than 1000 yards beyond the TBs. At 1206, Layton fired both of his bow tubes, then went deep to avoid the possibility of the TBs veering over top of him. The die rolls, however, just weren’t there; the torpedoes passed in front of S142 and the column of TBs, then slipped safely aft of the light cruiser.

Wintour now made the decision not to pursue Gaudecker, although confident he could have run him down given another thirty minutes. The odds had run in his favor this day, and he didn’t want to press it. If his overall objective was to get E13 back to base, then they should resume that effort once assured the German force would not return. HMS Christopher, still short of steam from her engineering damage, reaches the site of S141’s sinking to search for any survivors. None were found.

Over the years, we’ve fought some pretty large actions that involved upwards of 40-50 ships, and those have often been rather bloody affairs. These smaller battles, as seen in RotS II, tend to be more a game of maneuver, often relatively bloodless. After you’ve spent five or six hours on one of these, the lack of a clear result is often a bit frustrating. I’ve spent quite a bit of time trying to understand why this is, and I have a few ideas.

I think the first is the simple fact that each side has so few “assets” available. Players come to understand that the loss of just one or two ships can put one side or the other in a serious bind. As platforms decline in number, the gunfire starts to concentrate on fewer targets and it’s possible/likely for damage to accumulate even faster. For this reason, people grow skittish and tend to play not to win, but instead to not lose.

The other thing that seems to happen can be laid at the feet of the relatively small-caliber weapons that are employed. In RotS II, the largest gun on the table is the pair of 6-inch single mounts on Bonaventure; everything else is 4.1-inch or smaller. This is a situation where a player is not racking up lots of equivalent hits when sorting through the gunnery results, so damage tends to accumulate quite slowly. Degrading the enemy seems a long process.

Torpedoes were greatly feared by the WWI navies; whole flotillas were seen to turn away at the very threat of a torpedo attack. For the life of me, I don’t understand why. My experience with FAI and torpedoes is one of great promise yielding little in result. I’ve come to the conclusion that one would have to darken the sea with vast shoals of tin fish to raise the likelihood of achieving anything, and even then, I have my doubts. The mounts are small, the numbers are low, ranges relatively short; only a brilliant die roller is going to lay open a few hulls.

If this game (scenario) was one primarily of maneuver, the Germans had executed miserably. On numerous occasions Hamburg had found her line-of-fire blocked by an intervening column of torpedo boats, and more than once suffered flank shots by the pursuing Swift and Acasta. The disruption caused by the loss of S141 stayed with the German commander for the rest of the day, largely preventing him from getting his units back into a better tactical formation.

HMS Acasta.

Still, the game proved to be great fun; another stride back toward something that feels normal. A good friend of mine used to say, “You’re not lost as long as there’s gas in the tank.” With that in mind, we’ve decided we’re not done with the Frisian Islands.

PostScript

Erskine Childers, a native Englishman, soldier, naval officer, later an Irish nationalist and gun-runner, got himself shot at the age of 52, but his life, whether you agree with his politics or not, is an amazing but complicated tale unto itself. If you get a chance to read The Riddle of the Sands, do it; I think you’ll find it a great beach-read, or better, a good book for this winter while sitting in front of the fire on a cold evening. Lay in a box of wood, two fingers of Jameson, then settle in. Let me know what you think.