Second Battle of Gotland

5 October 1915

Twelve months into the war, the volume of iron ore shipments from Sweden to Germany was ramping up. Nearly forty percent of Germany’s iron ore supply would come from Sweden, and both the British and the Russians took a keen interest in interdicting this traffic. The loss of this source of material would undoubtedly crimp the Kaiser’s war-effort in problematic fashion, and the Imperial Navy looked to protect it.

In 1914, Sweden’s rail network was largely inadequate for landward transport of ore to its southern ports. It was unfortunate, as had the capability been there, the sea route would have been greatly shortened and its defense made substantially easier. There was an iron ore railway that had been completed in 1902 between Luleå and Narvik, but that was impractical for obvious reasons. So instead, ore destined for Germany was transported southeastward to various ports on the Gulf of Bothnia or the Northern Baltic, loaded aboard bulk carriers and converted freighters, than carried south to the ore terminals of Northern Germany. It was a precarious route of considerable length that provided the enemy numerous opportunities for interception.

Gotland is a large island that sits smack in the middle of the Baltic approximately 50 nautical miles south of Stockholm. A small naval facility was located on the island at Visby, and this was made available to the Germans as required. The route of the ore carriers passed on the western side of the island through a wide channel of some 40 nautical miles. For the Russian Navy, this offered a number of operational advantages, one being the relatively short striking distance from a number of its naval bases, a second being the constriction it offered for search and engagement, be it surface ships, submarines, or naval mines.

Sweden, a declared neutral, was ill-suited and reluctant to provide protection for the trade routes south, and since most of the commercial transport was German, it fell to the Kaiserliche Marine to defend them. At this point in the war, merchant ships travelled singly along the established route. Conceptually, it was the route that had to be defended, not the individual ships. This would change in the coming months, but for now, much like the North Sea and the Atlantic, it was all rather haphazard.

What follows is a posed encounter between the Kaiserliche Marine and the Imperial Russian Navy in October 1915, some three months after the First Battle of Gotland in July 1915.

Situation

In the closing days of September 1915, Rear Admiral Mikhail Bakhirev, commander of the 1st Cruiser Brigade, received orders to return to sea to provide cover for mining operations in the waters directly south of Gotland during the first week of October. A similar effort three months earlier had resulted in the Battle of Åland Islands (also known as the First Battle of Gotland), an engagement in which Bakhirev had seen a number of advantages frittered away in the confusion of battle. He pined for another crack at the Germans, and now it seemed he might get one.

Within the next 30-45 days, the sea ice would start to form in the northern reaches of the Gulf of Bothnia and the number of ore carriers making the voyage south would begin to decline. It was imperative for the Germans to see that the increasingly vulnerable lanes remain unimpeded for as long as possible. The Russians hoped to slam the door.

On the evening of 3 September, a message was received at Baltic Naval Station headquarters at Kiel from the weather station at Hoburgen reporting minelaying activity by Russian naval auxiliaries in the waters off the southern end of Gotland. These reports were corroborated by those of the Swedish torpedo boat Regulus, assigned to patrol the southern end of the strait between the island and the Swedish mainland. The information was relayed to the base at Danzig, where Konteradmiral Johannes von Karpf was soon ordered to sea.

There would now be two German operations underway simultaneously. Konteradmiral Albert Hopman with Prinz Adalbert (flag), Prinz Heinrich, and Bremen had sortied a few days earlier in a cover operation for German minelayers sowing a field off Östergarn on the eastern coast of Gotland. Von Karpf would sail with cruisers Roon (flag) and Stettin, together with a pair of destroyers to sort out the reported Russian activity southwest of the island.

Thanks to the German codebook captured by the Russians with the loss of SMS Magdeburg in August 1914, both they and the British (a copy having been provided to the Admiralty) were able to decipher most German dispatches well into 1917. Reports related to Hopman’s and von Karpf’s sorties were analyzed in the naval offices at St. Petersburg and relayed to the 1st and 2nd Cruiser Brigades. Bakhirev would sail with cruisers Oleg (flag), Bogatyr, and the recently recalled Askold on a sweep south of Gotland. Admiral V. K. Pilkina would sortie with cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov, and Aurora on a sweep of the eastern coast of the island.

For game purposes, four players were available, each assigned to one of the four commands. Yours truly was assigned to von Karpf’s command.

Day of Battle

Von Karpf slipped his moorings and passed out of the Westerplatte at 2030, 4 October. Hopman’s cruisers had departed two days earlier. Von Karpf’s column had Roon on the point followed by Stettin and destroyers G7 and G8 close behind. He set his speed at 15 knots with the intention of reaching the sweep area by 0930 the next morning.

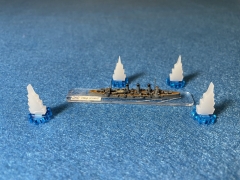

Von Karpf's force (SMS Roon, Stettin, G7, and G8)

Maintaining radio silence, the trek north was uneventful. At 2300, von Karpf ordered the destroyers to move up into positions 800 yards off Roon’s port and starboard bow. The moon was just a sliver in the night sky, so there was little light to silhouette the ships. Still, von Karpf feared the possibility of a submarine attack and hoped the destroyers out front would improve the chances for detection of any threat.

The eastern sky began to brighten with the first hint of sunrise at 0535. The column was proceeding north-northeast at 15 knots, still 50 miles short of their planned sweep location. At 0612, a faint smudge of smoke was observed on the horizon off Roon’s port bow. Von Karpf sent G8 to investigate while the rest of the column proceeded on course. At 0636, G8 signaled that they had spotted a Russian minelayer, the Narova, but that they had been unable to close to effective range due banks of morning fog. Von Karpf signaled G8 to return to the column, noting that the minelayer was quite far south of the targeted sweep area; after some consideration, he decided not to alter his course or amend his plans.

For his part, Bakhirev was barreling due west across the Baltic, having sailed down the length of the Latvian coast before making his westward turn. His column had Oleg on point, followed by Bogatyr and Askold, 400 yards apart, proceeding at 14 knots. Calculating their current position at 0512, the charts had them nearly 55 miles west-southwest of Sundre, the southern tip of Gotland.

Bakhirev's cruisers (Oleg, Bogatyr, and Askold).

At 0736, Stettin’s watch officer reported a faint smudge of smoke on the horizon off the starboard bow. The sighting was relayed to Roon where von Karpf made the presumption that whatever/whoever it was, it was almost certainly unfriendly, and ordered the due-north heading maintained while raising speed to 17 knots. Visibility was excellent, the morning haze having burned off, and the sea “gentle”, unusual for this time of year. The estimated range was in excess of 18000 yards.

Twelve minutes passed and the directors reported the target as three cruisers proceeding at an estimated speed of 12 knots, now at a range of ~ 15000 yards. Von Karpf ordered the column to turn ten degrees northwest to begin closing.

Bakhirev received the first report of a target at 0754, estimated at 15500 yards off his port beam and on a northwesterly heading. He ordered his column to maintain its speed and heading, aware that he would soon pass within two miles of the southern tip of Gotland, briefly limiting his ability to maneuver.

At 0806, von Karpf turns another eight degrees to a heading due northwest. With the range down to 12000 yards, he orders Roon to open on the lead cruiser. Not yet within her broadside arc, the forward 8.2-inch fires, missing short.

If the enemy is three cruisers, he knows he’s sorely outgunned. In an effort to distract and possibly divide his adversaries, Von Karpf orders the destroyers to attack the enemy column from the rear. At 0812, G7 and G8 raise speed and turn north.

Bakhirev sees Roon’s ranging salvo fall short just a few hundred yards from Oleg’s port side. Maintaining his speed and heading, he orders all three of his cruisers to concentrate fire on the lead German ship. No hits are scored.

Roon brings both of her twin 8.2-inch mounts to bear on Oleg, but they miss. Stettin manages a non-penetrating hit on Bogatyr, yielding minor hull damage (1/2 hull-box).

Roon brackets Oleg to no effect.

Von Karpf realizes this is the equivalent of a schoolyard fight; one has to hit the bully while he’s taking his coat off, otherwise the situation is likely to turn ugly in a hurry. He has advantages, however, primarily in Roon’s DCT fire-control. On this table, however, he also has disadvantages...he’s German and the dice here are routinely unsympathetic. Despite this, he continues, seeking some hits.

The next exchange yields little. Neither Roon or Stettin find their targets. Oleg manages another non-penetrating hit on Roon, inflicting no damage. Askold, on the other hand, becomes aware of the closing DDs and turns her 6-inch on the charging G7. One hit disables the destroyer’s forward 3.4-inch as she continues to close.

At 0824, Oleg takes a hit from Roon on the port side of her hull, just below the bridge. Flooding reduces her top speed to 20 knots. Oleg’s return fire misses, as does Bogatyr’s.

At 0830, Bakhirev orders Askold to turn out of line and raise her speed, coming around on the closing destroyers. For their part, the DDs turn a few degrees northeast, thereby taking themselves out of range for firing torpedoes. It’s a head-scratching maneuver, but it is what it is. Askold prepares to rake them with 6-inch.

Roon lands an 8.2-inch round onto Oleg’s deck into a ventilator just behind her forward funnel; there are a number of casualties but no significant structural damage. Oleg’s return fire lands a 6-inch that penetrates Roon’s hull (critical hit), disabling her forward engine room. The cruiser loses quite a bit of steam and her speed falls to 13 knots, her new maximum.

The German destroyers race across Bakhirev’s wake, 3800 yards astern of Bogatyr. They make a sharp turn to port, aiming to run the Russian cruisers down into torpedo range. Oleg and Bagatyr remain focused on von Karpf’s cruisers, while Askold tries desperately to get back to a position to engage the DDs.

But no sooner does Bakhirev signal Askold these instructions, he changes them, now sending her south to close on von Karp’s column from astern. Oleg and Bogatyr turn further southeast, running headlong toward von Karpf, allowing the German to “cross their tee” at 5700 yards. Roon puts another 8.2-inch into Oleg’s hull, crushing bulkhead 3A while further gashing her hull. Seawater pours in as her top speed drops to 15 knots. Oleg returns fire with her forward 6-inch, holing Roon again amidships. Askold lands a hit on Stettin’s aft starboard mount, disabling the 4.1-inch and killing the crew. Von Karpf wonders where his damn destroyers are.

Roon, firing everything at near point-blank range, misses the slow-moving Oleg. Oleg’s crew tries unsuccessfully to stanch the flow of seawater, but their efforts, at least for now, are unsuccessful. She continues firing at her tormenter, Roon, but misses at just 3400 yards.

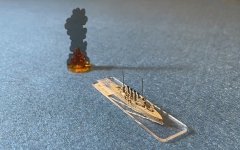

Askold puts a 6-inch round into Stettin’s hull, destroying a bulkhead and starting catastrophic flooding. Seconds later, Bogatyr hits her in her aft magazine; an attempt to flood fails and Stettin is destroyed in a massive explosion. There are no survivors.

Stettin is destroyed by a magazine hit.

As bits of Stettin rain down on Roon, von Karpf is left to take stock. His nightmare scenario has taken form, and now he needs to put some water between himself and the three Russian cruisers, hopeful that the destroyers return to provide a screen for his escape. The Russians continue to pound Roon, however, and she soon loses both of her main battery and suffers another hit into her forward engine room, slowing her precariously.

For her part, Roon resumes pounding Oleg. Another bulkhead hit and a further hull strike cuts her speed to just three knots, her deck nearly awash. She fails her morale check, and tries to inch away. At 0900, her last chance to repair the bulkhead damage passes without success and Oleg sinks under Bakhirev’s feet.

Moments later, Bogatyr lands a pair of 6-inch on Roon, yielding a ½-hull box and another engineering hit. This, together with her still unrepaired engineering hit, puts her dead in the water and disables her 5.9-inch secondary. She’s effectively a sitting duck.

The loss of Oleg and the unknown fate of Admiral Bakhirev, together with the rapidly approaching German destroyers, has Askold and Bogatyr breaking off and headed south. Minutes later, Roon is able to restore power and slowly begin to return home, escorted by G7 and G8.

Four hours later, the Russian minelayer Onega arrived on scene to recover Oleg’s survivors, a waterlogged Admiral Bakhirev among them.

Results

Two light cruisers lost, one Russian and one German.

Bakhirev had some success once he closed the range to 6000 yards (or less), but longer range fire was largely ineffective. Stettin’s 4.1-inch and her poor fire-control seemed to render her nearly useless. Roon, as is normal around here, suffered abysmal gunnery at the longer ranges.

German maneuver was poor, especially with their destroyers. They turned away at precisely the wrong moment, taking themselves out of the action for nearly forty minutes. The Russians‘ fear of a pair of DDs struck me as irrational. In my experience, only vast shoals of WWI destroyers should be feared, as individual DDs, or even small groups, frequently prove ineffective on the attack.

I’ve no idea what happened with Hopman’s force. My understanding is that the impatience of the German player had him wandering off to the north, never encountering any of the enemy. Presumably the Russians were able to sweep in and drive off the minelayers Hopman had been sent to protect. A dull time was had by that part of the game group.

I apologize for the tediousness of the narrative. The notes were quite convoluted, although we did produce a decent map of the force movements (see attached, if I can remember how).