Bremse/Brummer had an unusual appearance for German cruisers. With 4 guns all on the centerline and 3 round funnels equally spaced, they bore a passing resemblance to some of the British cruisers. As I understand it, in the actual action this caused some delay in the British escort recognizing them as German cruisers presenting a threat.

#201

Posted 07 June 2022 - 10:38 PM

#202

Posted 08 June 2022 - 08:29 AM

I agree, Bremse and Brummer are two very interesting ships. According to Scheer's memoir, they were originally contracted by and built for the Russian Government as fast minelayers, subsequently requisitioned and completed for the German Navy. Perhaps the centerline arrangement of their 5.9-inch mains was developed to accommodate the minelaying gear they deployed. Scheer described their mine capability as being more than double that of the other light cruisers (300-400 mines versus 120 mines). Trying to confirm their flank speed is tough. Most of the sources I have here indicate 28 knots (which is the top speed in the ODGW log sheets). However, I've seen notes claiming it could have been as high as 34 knots. My late-war copy of Janes doesn't list them at all.

Scheer also wrote that had the cruisers encountered nothing on the Lerwick-Bergen lanes, "they were to push on at their own discretion to the west of the British Isles into the Atlantic, as far as their fuel supply would allow." Now that would have been interesting.

- simanton likes this

#203

Posted 11 June 2022 - 10:06 PM

As I understand it, German warships - especially in wartime - ran their trials on a relatively shallow water course in the Baltic. Which meant that their speeds were retarded by "bottom effect" and they might well do better in deep water. On the other hand, I also understand that German domestic steam coal was inferior to Welsh. I do know that Kpt. Mueller of Emden was always hoping to capture a collier loaded with Cardiff coal.

- healey36 likes this

#204

Posted 12 June 2022 - 07:37 AM

Which leads to another generic question; my understanding is that the Brummer-class (along with a number of other classes in both navies) was designed and built with the capability of using coal or bunker oil for fuel. Does this mean that the ship had both tanks for oil storage as well as bunkers for coal storage concurrently, or is this a capability of the boilers to be fueled with either but requiring a minor "conversion" for storage to one or the other? I've looked at some blueprint-style line drawings of Brummer but I'm not smart enough to discern the configuration of her fuel storage "compartments".

- simanton likes this

#205

Posted 12 June 2022 - 08:11 AM

Interesting discussion Healey and Simonton.

- simanton likes this

#206

Posted 13 June 2022 - 02:52 PM

Interesting discussion Healey and Simonton.

Good place to learn a few things, for sure. These guys have saved me from a number of gaffes over the years.

- simanton likes this

#207

Posted 18 July 2022 - 06:35 AM

We've been working on a follow-up North Sea convoy action, specifically that of December 12, 1917, or thereabouts, but when I "floated" the idea to the players they were generally disinterested in such a small action (a dust-up of a half-dozen DDs and a few armed trawlers, squabbling over a half-dozen small merchants). They want the thing blown up to include much of the activity in the North Sea at the time. Both navies had a bunch of assets at sea, but as usual, encounters were virtually nil. So I pulled out the HFD Cape Matapan game we used as a basis for the grand operational slog a few years back, the idea being to see if we could use some of those concepts to develop something similar for the North Sea, early winter of 1917. The first task is to develop an operational map that covers two thirds of the North Sea, and we started work on that this past weekend.

It's conceptually difficult to figure out how to make this work. A lot of why there were so few encounters at sea was because no one knew specifically what the other guy was doing or where he was. Throw a few counters on a hex-grid map, and suddenly everyone has a pretty good idea what the other guy is doing and where he likely is. It seems arrival/departure intel was pretty good; everything in between, not so much. This was certainly true out in the Atlantic, but holds up much the same in that bathtub known as the North Sea. Sounds like two maps hidden from each other, along with an umpire might be the best solution.

More when I know it.

- simanton likes this

#208

Posted 19 July 2022 - 11:30 AM

While looking to replicate a more expansive take on North Sea operations, we needed to spend a few days trying to understand the aerial search capabilities of both navies in the last twelve months of the war. There’s a lot of information out there, but it seems much of it is mythology, at least from the perspective of effectiveness. History tells us that search patrols enjoyed a mixed bag of results, but in the big scheme of things, was largely inept.

As best I can tell, the Germans relied primarily on the naval wing of the Zeppelin force for patrol work over the North Sea. Despite the amount that has been written concerning the Zeppelins’ “strategic” bombing missions against Britain, it is overwhelmingly clear that the more mundane task of naval reconnaissance was their primary work. That said, it seems there was never more than a small handful, sometimes as few as one or two, on patrol duty at any given time. These numbers became even fewer as British anti-aircraft capabilities increased.

Fixed-wing patrol aircraft were largely absent from the German OB until late in the war, and then only in small numbers. Successful types such as the Hansa-Brandenburg W.12 floatplanes came online in mid-1917, but only a few, and these were relatively short-ranged and of short endurance.

On the British side, airships were also employed, but primarily in an anti-submarine role. The Brits overwhelmingly used non-rigid (blimp) technology for their fleet, this being better suited for slow speed and linger capabilities as compared to the Zeppelins. An NS-class (North Sea) was developed, entering service in early 1918, but these too were employed primarily for anti-submarine patrols and convoy-escort duties. Production numbers of the NS were small, with just 14 completed by the end of the war.

It appears that the RNAS had better results with their fixed-wing seaplane fleet. These were employed in patrol, anti-submarine, and anti-Zeppelin roles, and were fairly successful. The Curtiss H-12 and H-16 were arguably the best, going into service in April 1917 and March 1918 respectively. By war’s end, there were a combined 50 of the two types still in service. Given the RNAS employed nearly 150 H-12 and H-16 types over the course of the war, the attrition rate was high.

Compared to the Hansa-Brandenburg types, the Curtiss seaplanes had nearly 2-1/2 times the endurance and had a patrol range half again greater. However, when you consider that the North Sea is roughly a 1000 miles, north to south, and 400 miles at its widest point, one can begin to understand how equipment capabilities didn’t align very well with the vast patrol area.

So I’m left to wonder how they had much of any success in reporting the presence of enemy ships. I think the answer lies in the nature of their employment. It seems most of the Zeppelin reports were made by airships operating in conjunction with the surface fleet, i.e. they were sent out ahead of the fleet, almost serving a sort of picket role miles ahead. These weren’t just random patrol regimes in assigned areas, but typically missions ahead of major operations. On the other side of the house, there are relatively few reports of successful contacts in a recon role (although numerous reports of submarine sightings and more than a handful of Zeppelin downings).

- simanton likes this

#209

Posted 20 July 2022 - 02:34 PM

Draft of the strategic map:

Scale is approximately 11.25 nautical miles to the hex. Feel free to bogart the map for your own use.

- simanton likes this

#210

Posted 16 August 2022 - 11:25 AM

We’ve been working on the North Sea strategic map and scheme for a while, in between a number of other unrelated projects. The thing has taken on a bit of life unto itself, the scope having expanded to make it usable for the entire war. It’s become a bit of a slog, but the good news is we have a couple of players lined up to give it a run-through once we’re done trying to develop/kill it. We’ll see how it goes. I’m having flashbacks of the early sessions we had for ATO’s Artic Disaster, a board game that covered the PQ-17 fiasco.

I’m not happy with the map we developed, as we want a nice printed version but the graphics we came up with are too small. Being a hard-copy kinda guy, we need a larger version that can be printed on the standard twenty-two inch by thirty-four inch format (or something close to that). We can do it, it’s just a pain. For now, we’ve set that aside. Someone suggested developing a Vassal version, which is likely a good idea for the long haul, but I’m just not excited about teaching myself how to do it at the moment.

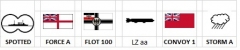

Using MS Paint and Excel, we made a few reusable markers (counters) for use with the map. Here are a few examples:

We tried to keep the descriptions generic so as to accommodate activity throughout the war. Serialization is just an alphanumeric assignment; specific unit numbers can be tracked on a separate track as required/desired. Custom counters could be produced using the Excel template if the players or umpire desire to do so.

We’re fortunate to have on-hand a plethora of naval board games and other rulesets, some of them 50-plus years old, others of a more recent vintage. At least three hail back to the interwar period. We did our reading chronologically, so we quickly got a sense of what operational aspects were considered critical by the developers over time. We cherry-picked the pile a bit, reading through a couple dozen to develop three things primarily: (1) how to track/regulate movement, (2) how to determine spotting, and (3) how to handle weather and its effects. Dunnigan's Jutland has a pretty simple operational-scale approach for the North Sea, tracking movement and search, and it, together with a few more recent games, was at the center of much of what we came up with.

Movement

Naval movement is really pretty straight forward. If you know ship speeds and the map and time scale, it becomes little more than a math exercise. There are, however, a few complications that arise once engagements occur and damage is taken; these I still need to sort through. The overriding principle, however, is that no unit can move faster than the slowest ship in the group. Naval units would be assigned movement factors based on the slowest ship in the group. Units where all ships have a flank speed exceeding 30 knots are assigned a movement factor of 3, meaning they can move up to 3 hexes on odd-numbered turns, 2 hexes on even-numbered turns. Units comprised of ships with a flank speed between 20 and 29 knots would have a movement factor of 2, meaning they could move two hexes per turn. Ships with a flank speed between 7 and 19 knots would have a movement factor of 1, meaning they could move 1 hex per turn. Ships with a top speed of 6 knots or less can move 1 hex on odd-numbered turns, 0 hexes on even-numbered turns. Units containing damaged ships have their movement factor adjusted to match that of their current top speed.

Zeppelins seemed to have had a patrol speed of around 50 knots. This would give them a movement factor of 4 hexes per turn. Endurance was roughly 36 hours, however, so how to regulate their time aloft? The German Navy, on average, seems to have had two Zeppelins on patrol at any given time. As it’s unlikely, at least initially, that any scenario will be longer than three days, maybe we can presume that German airships are on station for the duration. Weather could have a severe impact on their operations, and special rules for that will be included in the weather section.

Spotting Concepts

Replicating spotting has always been the thorn in the side of naval wargaming (at least in my experience). Unless you’re going to move to some sort of umpired double-blind system, you’re left with either the chore of executing/tracking a multitude of assets involved in the search by position, or moving to some sort of abstract system replicating intelligence gathering without all of the bookkeeping. For our purposes, I decided to go with a hybrid approach incorporating elements of both.

Back in the mid-1970s, I recall playing GDW’s Midway and Coral Sea games and the nightmare of “flying” aerial searches hex-by-hex until one stumbled onto the enemy position. It was painful and time-consuming. It was also nonsensical. Even back then, it seemed to me that search was inexact (as was so frequently seen historically), and that it would be best handled in some sort of abstract manner. I had no real grasp on how to do that, but I had a few ideas. However, a decade later came a little computer game for the Commodore 64 titled Carriers at War. The designers made the leap from the super-detailed search routines seen in the board games to a simple abstract search-launch algorithm that worked really well.

In Carriers at War, the computer handled the abstraction brilliantly. Similar to a real task force commander, searches were specified by their heading, the number of assets assigned to conduct the search, and the operating range of the outbound searchers. The search result, if it “found” anything, was typically in the form of a report. The report gave an approximate position and a manifest of what was sighted. The farther out the sighting, the less reliable the report. Ship numbers and types were frequently misreported the further out the contact was made.

Of course, nothing as complex as a search conducted by carrier-based aircraft needs to be contemplated for North Sea operations in WWI. Recon patrols executed by the Royal Navy Air Service could be handled abstractly. Catapult-launched floatplanes by cruisers and battleships was in its infancy, so for the most part, we disregarded it. Spotting, we figured, was primarily the result of head-to-head encounters and/or radio reports from the vast number of other surface assets at work within the confines of the North Sea at any given time (trawlers, drifters, submarines, mine-layers, mine-sweepers, the occasional merchantman, and other purpose-built patrol craft). Throw in the Zeppelins and the Royal Navy’s seaplanes operating out of their stations, and much of the North Sea seems pretty well blanketed. Of course in reality, that means little. Stuff was frequently still able to move without detection.

To make this all work, we were forced back into the double-blind system, one operated by an umpire. He/she will maintain a comprehensive map of the entire area tracking all surface units of both sides, Zeppelin positions, convoys and their routes, spotted-status of units, and weather conditions. Maps will also be provided to the opposing players to track their units, any spotted enemy units, detected convoys, and the weather.

After reading through numerous approaches taken by various designers, we came up with an operational game sequence boiled down from all of them. I’m sure we’ll find some holes once we get going, but for now the simple sequence of play and the simple operational rules look like this:

Sequence of Play (Operational)

- Weather – Weather determination, movement, and effects are executed.

- Spotting – Spotting is determined for all units on the map per the spotting rules.

- Movement – Units move at the owning player’s discretion up to their maximum speed.

- Combat – Units occupying the same hex where one or both units are spotted may be set up on the tactical table for engagement.

- Disengagement – Units that break off from combat are withdrawn one hex in a direction determined by the umpire.

- Turn Conclusion – Hourly turn marker is advanced and all spotted markers removed.

Weather

North Sea weather conditions were largely unpredictable and frequently severe. Conditions typically had an adverse effect on surface movement, spotting, tactical combat, and air operations. To create a sense of the weather’s impact, the following rules for conditions will be executed during the Weather Phase of each turn by the umpire and communicated to the players:

Creation/Movement

- Front formation - On the western map edge, six weather positions are noted A-F. Similarly, a storm/front marker is provided for each position A-F. The umpire rolls one d6 for each position; a roll of 1 results in the placement of the storm marker for that position. Multiple storm markers may be deployed simultaneously, but a storm may only be initiated from a position once.

- Front movement – Storm fronts move west-to-east. Roll one d6 for each storm marker on the map. The storm marker will move that many hexes in a northeasterly direction (even numbered die roll) or southeasterly direction (odd numbered die roll).

- Front markers that have moved across the entire map and off the eastern edge are discarded. There is no reuse of front markers.

Effects

- Weather effects on spotting (see specific die roll modifiers for spotting impact in the spotting rules).

- Tactical combat initiated in a front hex will have Force 7 sea conditions. Tactical combat initiated in one of the six hexes surrounding a front will have Force 5 sea conditions. Non-front (clear weather) hexes are considered Force 4 sea conditions.

- Following front movement, any zeppelin in a front hex or one of the six surrounding hexes rolls a d6. A result of “1” destroys/disables the zeppelin and it is removed from the map.

Spotting

Spotting is an abstract process designed to give players general intel on enemy positions across the strategic map. Only positional intel is provided, i.e. a report of warships or merchant ships detected at a specific position, but no detail regarding numbers or types. If it is a convoy, that should be disclosed. Spotting reports are considered an hourly process and are deemed qualified for one hour.

The process for determining and communicating spotting is as follows:

- The owning players will roll one d6 for each of their units at sea. A modified roll of “1” or “2” results in a spotting report for that unit. The die roll is modified as follows for various conditions (all modifiers cumulative):

+1 if a night turn.

+1 if unit is in a storm/front hex or one of the six surrounding hexes.

-1 if it is a German unit within ten hexes of a Royal Navy Air Station (RNAS).

-1 if it is a British unit within three hexes of a zeppelin.

-1 if within five hexes of an enemy surface unit.

-1 if in or adjacent to a hex containing an enemy surface unit.

A d6 roll of “6” is always a failure to be spotted, regardless of modifiers.

Units in a coastal hex are automatically considered spotted.

- The owning players will alert the umpire as to which of his/her units have been spotted. The umpire will mark these units on his control map with spotted markers and will communicate the position of these units to the opposing player. The British and German player should put a spotted marker on (1) the reported positions of enemy units, and (2) may also want to put spotted markers on their own units if spotted for reference purposes.

- At the end of the spotting phase, each player should have a comprehensive situation map that provides the position of all weather, all of his own units, plus the position of all enemy units that were spotted during the phase.

Movement

Movement is considered simultaneous and is executed by each player on their strategic map. Units are moved up to but not exceeding their movement factor. Movement factors are determined as follows:

- Units where all ships have a flank speed exceeding 30 knots are assigned a movement factor of 3, meaning they can move up to 3 hexes on odd-numbered turns, 2 hexes on even-numbered turns.

- Units comprised of ships with a flank speed between 20 and 29 knots would have a movement factor of 2, meaning they could move two hexes per turn.

- Ships with a flank speed between 7 and 19 knots would have a movement factor of 1, meaning they could move 1 hex per turn.

- Ships with a top speed of 6 knots or less can move 1 hex on odd-numbered turns, 0 hexes on even-numbered turns.

- Units containing damaged ships have their movement factor adjusted to match that of their current top speed.

- Zeppelins may move up to four hexes per turn, but may not move into storm/front hexes or the adjacent six hexes.

All movement is communicated to the umpire who will replicate it on his control map. No changes to spotting status occur as a result of movement. Movement of spotted units is communicated to each opposing player and the positions of spotted enemy units are noted on their operational maps. Spotted units that end their movement phase in an enemy occupied hex can be engaged for tactical combat at the discretion of the opposing player.

Tactical Combat

If engagement is made, the spotted unit is set up at the center of the table directionally (determined by the umpire) and in a formation chosen by the owning player. The opposing (approaching) player places his units on the table directionally (determined by the umpire) at an opening range of 15000 yards (or less if the umpire deems the weather conditions to be such that visibility, or lack thereof, would allow a closer approach). If both units are spotted, a d6 is rolled to determine which force will be set up at table center (highest result gives a unit the center position). At this point the tactical rules of FAI take over.

The engaged units remain in the hex on the operational map until a conclusion to the action is reached. At the top of the hour, a new turn is executed on the operational map while the battle rages on the tactical table. The umpire may deem that the action has moved to an adjacent hex based on movement of ships on the tactical table. This is a discretionary determination left to the umpire.

It is possible that additional units might enter the tactical table based on the movement of units on the operational map. This possibility will be managed by the umpire. For spotting purposes, all units actively engaged are considered spotted until disengaged.

Disengagement

Disengagement occurs when one side is able to outrun the other on the tactical table, or when both sides announce a mutual decision to disengage. The disengaging unit is removed from the table and moved to an adjacent hex on the operational map, directionally in concurrence with the umpire. If a mutual decision to disengage is made, both units are moved to adjacent hexes, directionally as prescribed by the umpire. Unit speeds are adjusted/noted to reflect battle damage.

On occasion, a convoy will be dispersed in the face of an overwhelming attack. In this case, the convoy’s charges will be moved independently in an effort to leave the tactical table in a multitude of directions. Any ship that moves off the table is considered to have escaped. When all convoy ships have been exited or sunk, or if both players mutually agree to disengage, the convoy is considered dispersed and is removed from the operational map.

Turn Conclusion

At the end of the operational turn, the turn track is advanced to show the completion of the current one hour turn. All spotted markers are removed (with the exception of units actively engaged in a single hex).

Any thoughts/suggestions are welcome. Keep in mind it’s intended as an abstract approach. I’m sure playtest will expose numerous holes. I apologize in advance for gaffes in the format here...always a challenge moving from MS Word to the forum.

- simanton likes this

#211

Posted 16 August 2022 - 11:45 PM

Reminds me of the one effort I am aware of in a commercially published game to incorporate all of these elements, which was Taurus Ltd's "Raiders of the North" of 1974. Sadly, I was never able to line up fellow gamers to really try it out!

- healey36 likes this

#212

Posted 17 August 2022 - 07:54 AM

You're likely not going to believe this, but I actually had a copy of Raiders of the North many years ago. I sent it to a friend of mine, an epic naval wargames collector, to help him fill some gaps in the collection. RotN, as I recall, was one of those games I liked to pull out once in a while just to look at it, read the rules and the designer notes, then put it away as it looked unplayable. I don't recall ever contemplating an attempt to actually play it. Taurus, the publisher, fancied themselves a bit of a think-tank and designed their games based on some pretty esoteric research (IMHO). There were a number of games in their catalog, including a few other naval topics, but the one I really wanted was a simulation of the WWII Axis invasion of Albania and Greece. I don't recall if that one was ever actually produced, but the ads looked really promising and it was a topic of interest for me at the time.

Flattop was another killer. I have the original version by Batteline, and I think I ruined it by drooling on it. I believe the rulebook was bigger than my hometown phone directory at the time. I recall a three or four page section of the rules laying out the procedure for arming and fueling strikes. A brilliantly researched and produced game, but hopelessly unplayable, at least in my experience.

Wow, "hometown phone directory"? I'm showing my age.

- simanton likes this

#213

Posted 20 August 2022 - 12:26 PM

A question came up regarding the strategic map and the positions of and effects of minefields in the North Sea. Something certainly worthy of consideration, but where were they? Found this 1918 map over in the Library of Congress that might be useful:

- Kenny Noe and simanton like this

#214

Posted 22 August 2022 - 08:58 AM

The 1918 map may be pretty useful for the last year of the war, but the minefields were likely far less extensive and organized before mid-1917 (except for those near Heligoland and across the approaches to Wilhelmshaven, Cuxhaven, and the Frisian Islands). A good example is the North Sea Barrage that stretches from the Norwegian coast toward the eastern approaches to the Orkneys. Its deployment was largely an American effort overseen by the British in 1918. It's often confused with the Royal Navy's Northern Barrage, a network of fields primarily located off the northern coast of Scotland. Ireland, reaching as far west as Iceland and the Denmark Strait. Reading Scheer and Beatty's notes, it seems that the effort to bottle up the HSF via mine belts really ramped up during the last 12-18 months of the war.

It's something we're going to have to deal with in our operational approach. Wandering through the mine belts was often lethal, even if a ship stumbled into its own fields (see SMS Yorck, for example). The fields had various characteristics: depth, density, contact or magnetic, drift or anchored, etc. Not a lot of detailed info to be found, so some supposition likely required.

- simanton likes this

#215

Posted 31 August 2022 - 11:08 AM

Okay, so we've edited the North Sea strategic map a bit, now noting approximate minefield positions during the late-1917 and early-1918 period:

The British minefields are in red, German minefields in black. We started with Furlong's map from August 1918, then tried to work backwards to an approximation of what things might have looked like in December 1917. To flesh out Furlong's box along the western Danish coast (we couldn't find a copy of the detail map alluded to on Furlong's grand map), we compiled a list of some forty minings reported in various sources during the second half of 1917, then plotted their approximate positions on a map. This, together with some reading on the RN's intentions/designs on mine-laying, and we came up with what we think is representative of the situation. It's a leap, for sure, but likely/hopefully not an horrifically inaccurate one.

An interesting thing we learned (which seems intuitively obvious in hindsight) was that fields were sown with one of two intentions. Either they were for protection or they were to block or channel passage. The dense German fields in the southeastern corner around and south of Heligoland were strictly for protection. This was also true for the fields sown by the British along their eastern coast where they maintained north-south convoy routes. The British fields sown across swathes of the central North Sea and along the Danish coast were intended to channel movement, the idea being one couldn't cover everything, but by blocking some areas, the amount of sea that had to be actively patrolled was theoretically lessened. It was also intended to help with the blockade of German ports. Some of the British ports on their eastern coast had extensive local fields, but for our purposes, we left those off the map.

I'm leaving the mine warfare rules-writing to those in our group who insisted we needed to consider it ![]() . My only request was that they keep it simple. I'm hoping to get a draft of that sometime in the next couple weeks.

. My only request was that they keep it simple. I'm hoping to get a draft of that sometime in the next couple weeks.

- simanton likes this

#216

Posted 03 September 2022 - 06:29 PM

Despite my best efforts to avoid it, I got drawn back into the mine warfare rules-writing process and it was just as ugly as I anticipated. It seemed the convened group had reached loggerheads within a relatively short period of time and needed some heavy-handed input to gain traction. No worries, those are skills I honed during a 37-year career in corporate finance (although back then it usually involved a locked conference room and a medicine ball ![]() ). Their process for writing these rules at the operational level can be best described as akin to legislative sausage-making. My request that they come up with something relatively simple seemed to have gone by the wayside. Many concepts and related details were offered for consideration, way too many, and it took the better part of a Saturday to hash through it and trim it down to something manageable. What we came up with was something that no one seemed completely pleased with, but generally accepted as reasonable.

). Their process for writing these rules at the operational level can be best described as akin to legislative sausage-making. My request that they come up with something relatively simple seemed to have gone by the wayside. Many concepts and related details were offered for consideration, way too many, and it took the better part of a Saturday to hash through it and trim it down to something manageable. What we came up with was something that no one seemed completely pleased with, but generally accepted as reasonable.

The one thing I needed to get my own head wrapped around was the lethality of mine warfare during WWI. That, it seems, is easier said than done. There’s a ton of information out there, but little concurrence as to mine effectiveness. If some sources are to be believed, the Royal Navy laid close to 200,000 mines during the war, roughly 35% of those in the North Sea Barrage which was developed in mid-1918, together with a substantial number laid as part of the Dover Barrage throughout the war. For the HSF, I’ve seen numbers of a bit less than 50,000, half of those in the vast fields which extended out into the North Sea some 40 to 50 miles to guard the approaches to their naval bases on the Elbe and the Jade. German naval losses during the war attributed to mines, excluding merchant ships, seems to have been about 150 vessels, nearly a third of those submarines. For the British, a bit higher, and quite a few of those being more noteworthy. When you run the numbers, however, ships lost versus mines laid, the risk doesn’t feel oppressive.

That, of course, can be deceiving. A number of the fields laid by the RN targeted U-boats, so many mines were laid at varied depths surface ships could sail over unimpeded. The other thing to be mindful of is that defensive fields seemed to have been less effective, i.e. generating fewer casualties, while fields laid in well-travelled enemy waters produced higher losses (HMS Prince Edward VII and HMS Audacious being a couple of good examples). The Germans seemed particularly adept at this, the British not so much. In the end, however, it seemed the effect of mining the North Sea was far more psychological than perilous.

So now back to the rule-writing. From the outset, there was reluctant agreement that the overriding goal was to produce a simple set of rules for ships that entered friendly or enemy minefields on the operational map, either intentionally or unknowingly. In so doing, a number of related subtopics were presented, then discarded, and some folks weren’t happy about it. It became a task of beating down the minutiae (and the opposition).

First up, we agreed that mine-laying and mine-sweeping were off the table (if one wanted to have a go at that, someone could write a separate scenario and have at it using the rules as written in FAI). Our focus was fleet sorties and the effect of encountering mines, not how to introduce or mitigate their presence. All of the talk of leading sweeps, paravanes, sweep wires, etc., were tabled. That discussion only took an hour.

The next topic was drift mines, a pet concern of my own. There are numerous accounts of ships, mine-sweepers, and patrol craft encountering random mines free-floating across the North Sea, but examples of casualties are scarce. Further reading indicates that many of the mines drifting in open water were those whose mooring cables had broken or been cut during sweeping operations. More importantly, drift mines were banned by the Hague Convention of 1907 and it seems, for the most part, to have been observed by both navies (although there was some work at development of a hybrid; see Leon Mine). At the end of the day, consideration of random mines floating across the vastness of the North Sea and the risk they posed seemed de minimis and the topic was discarded.

Other issues were raised and cast aside, one-by-one. The last concern was differentiation between moving through friendly (?) or enemy minefields. One proposal saw friendly ships moving through friendly fields unimpeded, but that didn’t feel right as there are numerous examples of ships sunk or damaged by a friendly mine not where it’s supposed to be, or a ship wandering outside its “safe” channel and onto the edge of the deployed field. In the end, we decided to try a +1 DRM on the Mine CRT if suffering a mine attack while passing through a friendly field.

Rules for Mine Warfare (Operational Map) – Rev. 1 Playtest

These rules pertain only to ships or groups of ships moving into minefield hexes noted on the operational map. Moving from one minefield hex to another repeats the process. Minefields are not hidden, as minefield locations are considered “generally” known; players can avoid them in their movement on the operational map. These rules allow mine attacks to be executed without moving ships onto a tactical table. Spotting has no additional effect on ships moving through a minefield. If contact is made between one or more spotted opposing forces in a minefield hex, all forces are moved to the game table and the umpire will conduct mine warfare in accordance with the rules as outlined in FAI, Section 7.16.

When a unit alone moves into a minefield hex on the operational map, the unit is segregated into its respective divisions, squadrons, flotillas, etc. Division/squadron flagships are assigned to an appropriate division or squadron by the owning player at his/her discretion. Ships of each division/squadron/flotilla, including assigned flagships, are placed on a column of the Mine Warfare Table, one ship to a box, at the owner’s discretion. If the division/squadron/flotilla has four ships in it plus a flagship, place the five ships one to a box in the first column. Ships may be placed in any box in a column. Once all of the ships have been placed, roll a d12. Cross-reference with the boxes, and if a ship is in the box corresponding to the die roll, that ship is considered to have crossed at least one mine row and is subject to a mine attack for each row crossed. To determine how many rows were crossed, roll the d12 again. A roll of 1-4 is one row, 5-8 is two rows, and 9-12 is three rows. All other ships in the division/squadron/flotilla are considered to have not crossed a row and are returned to the owner. A mine attack is executed for each mine row crossed by the ship, in accordance with FAI Mine Attacks, rules section 7.16.4.

It is highly unlikely that any division/squadron/flotilla is comprised of more than twelve ships, but if so, place the additional ships in the second column on the Mine Warfare Table at the owner’s discretion. This column will be cross referenced with the d12 result above. If the box in column b is also occupied on the d12 result, this ship is also considered to have crossed at least one mine row and the above process is repeated for the second ship.

If the mine field entered by the unit is a “friendly” field, add one to the die roll on the MINE CRT; if an enemy minefield, no adjustment is made. Damage is determined using the MINE & TORPEDO DAMAGE table as per FAI section 7.16.4, with all damage recorded on the appropriate ship’s log. Be sure to note damage affecting unit speed and adjust accordingly for movement on the operational map.

This process is repeated for each division/squadron/flotilla comprising the unit. When all division/squadron/flotilla have passed through the above process, all attacks resolved, and all damage recorded, the unit can resume movement as appropriate.

Example of play

In September 1917, Hipper is dispatched with his First and Second Scouting Groups to execute a sweep of the central North Sea, to pass across the northern edge of Dogger Bank before turning southeast to return to Cuxhaven in six days’ time. Early on the second day he receives a report from the umpire that a German minesweeper operating 50 miles north of his planned course has spotted a British light cruiser force on a north-northwest heading, proceeding at fifteen knots. Standing on the bridge of Lützow, he checks the charts and alters his current course and speed hoping to intercept the next day. Second Scouting Group, comprised of light cruisers Frankfurt, Stettin, Elbing, and Pillau, are approximately 30 miles off his starboard bow, operating as his screen.

Early the next morning, Hipper orders Boedicker and his Second Scouting Group to increase speed to flank in an effort to head off the British cruisers from the east. Boedicker realizes this will take SSG across the southern edge of a British minefield approximately 156 miles east-northeast of Scarborough, but to briefly turn west to avoid it will almost certainly preclude his being in position to block the British cruisers’ course. Hoping for the best, Boedicker plunges into the field at flank speed. At 1106, the umpire confirms that the German player’s Second Scouting Group has entered the minefield and should deploy his ships onto the Mine Warfare Table:

The German player places Boedicker’s ships in boxes 1, 2, 4, and 7 and rolls a d12, result of 4. This results in the determination that Elbing has crossed at least one mine row. The German player rolls the d12 again, the result a 6, indicating that Elbing has crossed two mine rows and must endure two mine attacks using the Mine CRT. He will roll a d12 twice. This is an enemy field, so no modifier. The first mine attack die roll is an 8, passing through the row without detonating a mine. He then rolls the d12 again, this time the result is a 2, resulting in a mine detonation. The German player now rolls a d12 and consults the HSF Mine & Torpedo Damage Table. The result is a 9; Elbing is destroyed by a massive explosion that breaks the light cruiser’s back, sending her quickly to the bottom with few survivors (this guy rolls dice like I do).

Boedicker continues northwest with his remaining three cruisers, but within two hours Hipper radios to say that his battlecruisers have been spotted and he is breaking off pursuit to return to base. Boedicker immediately orders his cruisers around to the south, now approximately fifty miles due north of the rapidly retreating Hipper, hopeful that he won’t be run down from behind by Hipper’s pursuers.

- simanton likes this

#217

Posted 08 September 2022 - 08:48 AM

A few tweaks in process for the mine warfare rules. After one play-test, the players felt the rules were (1) a bit arbitrary, and (2) possibly too bloody. I'm not sure one can make that assertion after a single test, but I would agree that the conceptual risk of moving through a friendly field seems exaggerated.

It'll be good to have this sorted and we can get back to the table for a real run-through.

More when I know it.

- simanton likes this

#218

Posted 04 October 2022 - 01:57 PM

No changes to the mine warfare rules at this time. This reinforces the notion that if one chooses to plow headlong through a field, friendly or foe, you get what you deserve.

Folks are still hung up on drift mines and pop-up fields, i.e. relatively small uncharted fields sown ad hoc by U-boats, commerce raiders, etc. Numerous ships were victims of the latter, but simulating them without just making it a haphazard, infinitesimal risk seems less than worthwhile. It also creates a bookkeeping nightmare for the umpire. Unless someone comes up with an elegant suggestion, we're likely to pass, for now.

The focus will be on December 1917 for this first run-through. The OB is in development.

- simanton likes this

#219

Posted 04 October 2022 - 11:22 PM

Sounds like you are sticking to a common sense approach!

#220

Posted 05 October 2022 - 08:06 AM

Playability is the key. I suspect this first run will involve multiple days/weekends if folks truly have the fortitude and commitment to play it operationally.

There was a lot going on in the North Sea from mid-1917 into the spring of 1918. By this time, it seems the British had a fairly sophisticated convoy system running up and down their east coast, together with the Scandinavian convoys which grew to be rather numerous. These attracted the attention of surface raiders as well as the U-boats, and of course, there were still vast numbers of trawlers/drifters working the fishing banks. This, however, seems a sideshow to the efforts made by the RN to lay/defend their minefields and the HSF's efforts to survey/sweep them. This had been going on for quite some time, but as best I can tell, it really ramped up as the German Navy became increasingly constricted. Second Heligoland is a good example of how things could escalate.

One thing for sure, there were a lot of assets at sea at any given time. There might have been little chance of a Second Jutland, but there was ample opportunity to beat each other up incrementally. Hopefully we can come up with something that feels like that without creating a giant hairball.

- simanton likes this

Also tagged with one or more of these keywords: FAI

Fleet Action Imminent Forum →

Comments, Discussions & General Q&A →

Firing on small craft FAIStarted by Swagman1982 , 14 Feb 2019 |

|

|

||

Fleet Action Imminent Forum →

Comments, Discussions & General Q&A →

Swedish Navy WW1Started by Mel Spence , 23 Sep 2015 |

|

|

1 user(s) are reading this topic

0 members, 1 guests, 0 anonymous users