I should clarify that my intention was not to denigrate Vice Admiral Schofield's work, just that I've found his accounts centered around planning and the administrative/logistical "back-office" of the Admiralty more interesting than his writings concerning his time at sea (which was considerable). This was a guy who commanded BB King George V in the latter stages of the war (WWII), so one might think it would be the opposite.

#161

Posted 10 March 2021 - 10:28 AM

- simanton likes this

#162

Posted 10 March 2021 - 12:58 PM

I have always been impressed with his writings.

#163

Posted 11 March 2021 - 03:21 PM

And then, here in Baltimore, we have Constellation, not THE Constellation (as we were led to believe when I was in grade school), but the sloop built in 1854.

It should be noted that there is still to this day a cadre of folks who remain wedded to the notion that the Constellation berthed in Baltimore's inner harbor is actually THE Constellation, but as she was rebuilt from a second-class frigate into a sloop of war (an 1853 redesign by John Lenthall, Navy Chief Constructor). Geoffrey Footner, a former WWII U. S. naval officer and local maritime historian, wrote an extensively researched 350-page book, USS Constellation: From Frigate to Sloop of War (2003), which detailed the ship's four rebuilds, together with her extensive operations. It seems a stretch, in my opinion, especially when considering the extensive "restoration" she's received incrementally over the past four decades, but if one buys into Footner's argument, then there would seem to be some credibility in the claim that this ship is indeed the nation's oldest surviving warship.

This might be a topic best suited for a Post Captain aficionado.

One last note - a mate of mine reached out to "remind" me that Constellation's spars and top-side rigging have been restored, and that I need to get out more. I would agree.

https://www.history....llation-ii.html

- simanton likes this

#164

Posted 29 March 2021 - 12:13 PM

Three Days of the Seagull

January 15-17, 1916

Desiring a distraction from the North Sea, I’ve been spending a lot of time of late reading up on the war on the open Atlantic (and Pacific). The surface actions there are much smaller in scale tactically (i.e. number of ships on the table) as compared to the great sparring matches conducted in the waters immediately separating Britain and Germany. The Mediterranean remains largely a mystery, one yet to be explored.

The idea of gaming commerce raiding by surface ships seems counterintuitive at the tactical level. A high percentage of the actions would encompass an auxiliary cruiser stopping and scuttling a merchant ship. That’s not exactly pulse-racing stuff. There were, however, actions that entailed armed merchant cruisers (AMC), armed merchantmen, auxiliary cruisers, Q-ships, and traditional naval ships, overlaid by the uncertainties of limited intelligence, training, the wireless, weather, and a healthy dose of luck, good and bad.

I had originally planned a quick two-ship solitaire game of the events of January 16, 1916, a simple exploration of commerce raiding as executed by SMS Möwe and her master Graf Nikolaus zu Dohna-Schlodien during their first voyage, but I soon decided to expand it to include the day before and the day after. A sort of mini-campaign of commerce-raiding, these three days seemed a representative snap-shot of Dohna-Schlodien’s methods, highlighting the opportunities presented, seized, and/or dismissed by the Royal Navy. Before throwing ships on the table, however, I wanted to better understand how things had gotten to this point. Here’s my rather long-winded take on the general situation and Möwe’s initial exploits.

SMS Möwe, location and year unknown. Likely a war-time photo, she appears to have her false masts raised. A Gazelle-class light cruiser is moored behind her.

The Kaiserliche Marine (KM) was founded as the linchpin in proving Germany a great imperial power, one that had global reach and strength. It was a departure from Bismarck’s Central European notions and disinterest in territories overseas. This shift came in the last years of the 19th century, with the Kaiser and Chancellor Bülow calling for territorial expansion, while others such as Admiral Tirpitz, argued for the product of German industrialization be dedicated to this end. This, of course, would bring Germany into direct confrontation with the greatest of imperial powers, Great Britain.

Tirpitz reportedly believed the inevitable clash with Britain was unlikely until 1918-1920, giving him scarcely two decades to provide the build-up of the German fleet. It was a tall order, but one he nearly pulled off, moving the KM from the sixth largest fleet in the world to one being second only to Britain’s Royal Navy. It’s important to note that, while Tirpitz’ creation may have been second in terms of numbers, many naval historians consider the KM’s assets to have been, pound-for-pound, superior to those of the RN. The real problem for Tirpitz was one of geography.

It’s interesting that Tirpitz called for the build-up of the fleet with an eye toward supporting Germany’s territorial expansion, yet failed so badly in providing for it. The bulk of his efforts went toward challenging Britain in the North Sea and breaking its presumptive blockade, while doing little toward the likely possibility of having to enforce one themselves. This failure was not only one of assets, but also the development of a logistical network capable of supporting a war beyond German coastal waters and the North Sea.

The failure, despite a lot of hard work, to develop adequate coaling and resupply arrangements with neutral or otherwise non-belligerent countries would prove disastrous. While some of this can be laid at the feet of a largely inept German diplomatic corps and the inattention of Tirpitz and his staff (Imperial Naval Administration), it was Britain’s aggressive strategy of “bunker control” which provided the British the ability to restrict/ration access to fuel for international commercial shipping and naval vessels. In August 1914, Britain had a network of 181 coaling stations around the world, nearly all well-developed and in favorable locations. The Germans had nothing so robust, and within months of the war’s start, the slim network of coaling stations they had assembled had begun to unravel. This forced the KM to rely upon a support structure consisting nearly exclusively of auxiliary colliers and depot ships, the operation of which would prove tenuous.

The prewar plan for commerce interdiction centered on the construction and use of a fleet of cruisers, operating across the globe, supported by a network of land-based coaling stations and, where required, colliers and supply ships. To this end, the decade or so prior to the war saw the construction of a substantial number of light cruisers, many of which were intended for commerce interdiction. However, with the war breaking out years before Tirpitz’ plan anticipated, the strategy ran afoul of competing priorities within the Navy and the general build-up of the fleet. Far fewer light cruisers were built than planned, and of those constructed, many were assigned to the High Seas Fleet’s scouting squadrons. Those which did operate as commerce raiders did so with some success before being hunted down and destroyed (see Emden, Karlsruhe, Königsberg, and to a lesser extent Dresden). Liners converted to armed merchant cruisers (AMC) also figured in German plans, but they, together with the light cruisers, proved expensive to build, operate, and ultimately lose.

The experiences during the first year of the war led to a thorough reassessment of the plans for commerce interdiction. The U-boats were quite few in number and, despite a handful of successes, there remained considerable skepticism regarding their ultimate capabilities. The submarine was still seen as a recent technical development by most naval theorists, and the very traditional-minded KM leadership remained strongly wedded to the surface fleet. While an expanded submarine construction program had been commenced within months of the war’s outbreak, the number of boats at sea were few. Until those numbers could be substantially increased, the navy’s strategy of interdiction, what little there was, would continue as a function of the surface arm.

The poor logistical situation, together with the inefficiencies of operating coal-hungry AMCs and light cruisers, drove the KM to quickly move the surface raider program toward the use of relatively modern cargo ships converted to auxiliary cruisers (Hilfskreuzer). These were relatively plentiful, generally small in size, economically efficient, and able to operate in an “anonymous” manner. While fast enough to overtake most merchantmen, they were unlikely to outrun a warship. They were, however, armed sufficiently to engage small unarmored warships if encountered, an eventuality thought to be unlikely. Because they were plentiful, inexpensive to build/convert, and quite efficient to operate, they were seen by some at the Naval Office as expendable. SMS Möwe and her sisters were the product of this operational course-change.

__________

My initial glimpse of SMS Möwe (alternatively SMS Moewe) came a few years ago while plowing through newspaper clippings, researching an unrelated topic. In the August 23, 1956, issue of the New York Times, I saw a short article announcing the passing of 77 year-old former Korvetten-Kapitan Burggraf Graf (Count) Nikolaus zu Dohna-Schlodien, the commander of a WWI German commerce-raider, which, according to the New York Times, “sank 200,000 tons of shipping in 1915-1917”. Presuming that the typical tramp steamer of the day was quite a bit less than 5000 tons, it seemed a rather remarkable score for both a ship and master I’d never heard of. The clipping went into a folder for later reference.

It turned out my initial impression was warranted. A bit more reading revealed that Möwe did indeed produce an impressive record, one that exceeded 40 enemy ships sunk during just three sorties (some sources credit Möwe with up to seven voyages, but this seems unlikely), including the old pre-dreadnought battleship HMS King Edward VII (by a mine laid by Möwe). Her record of success is deemed best of any commerce raider in either war. She ran the blockade three times, out and back, which itself is quite a feat when considering the strength and numbers of the Royal Navy’s blockade. While Dohna-Schlodien was clearly a skilled commander, Möwe seemed imbued with considerable good fortune.

She was built as the refrigerated freighter Pungo, launched in 1914, one of the famed “banana boats” operated by the Laeisz shipping company between Germany and its colony of Kamerun (today’s Republic of Cameroon). A year later she was requisitioned by the German Navy and renamed Möwe (Seagull), first for use as a tender, then converted into an auxiliary cruiser at Wilhelmshaven, commissioned as such in November, 1915.

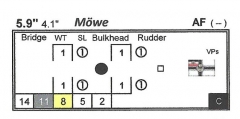

A list of her armament seems to vary somewhat by source, but the consensus seems to be four deck-mounted 5.9-inch naval guns, a single stern-mounted 4.1-inch naval gun, and either two or four deck-mounted single 19.7-inch torpedo tubes. She could also carry up to 500 mines. For the purposes of disguise, the 5.9-inch were hidden behind collapsible partitions, and the 4.1-inch was disguised as deck-gear on her stern. The crew had the ability to alter the height of her masts, and she carried paint and materials such that they could significantly alter her structural appearance (even to the point of adding a false funnel).

In the eyes of her KM handlers, she had one huge operating advantage. As a former freighter, her relatively low speed together with enlarged bunkers filled to capacity gave her a vast operating range. She would be sent on her way, requiring little and promised same, a throw-back to the days of nationally-sanctioned piracy on the high seas.

Her commander, Nikolaus zu Dohna-Schlodien, was born April 5, 1879 at Mallmitz, an industrial town in Lower Silesia. The fifth of five children, he joined the Kaiserliche Marine in 1896 shortly after his seventeenth birthday. Within six years he had been promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant (Oberleutnant zur See). He would serve aboard the battleships SMS Wittelsbach and SMS Braunschweig before receiving his first command in 1910, the river gunboat Tsingtau of the East Asian station. In 1913, he was made navigation officer of battleship SMS Posen, with the rank of Korvetten-Kapitan. In 1915, Dohna-Schlodien was transferred to the Hilfskreuzer program (overseen by Admiral Hugo von Pohl, who was terminally ill with liver cancer at the time), where he either chose or was assigned the converted Möwe as his command.

Möwe departed on her first cruise in the last days of December, 1915. Her point of departure is variously attributed to Wilhelmshaven (site of her conversion and commissioning) or Kiel, which are technically both correct, as it is likely she departed the yard at Wilhelmshaven, then passed through the recently-widened Kiel Canal to reach the naval base at Kiel. By so doing, Möwe avoided the extensive minefields off Cuxhaven and the onerous, dangerous task of sailing up and around the western Denmark coast. From Kiel, she would instead pass through the Skagerrak into the North Sea, where she could proceed surreptitiously along the southern Norwegian coast before heading west. It would be the first, and not the last, demonstration of Dohna-Schlodien’s considerable navigation skills during his commerce raiding career.

At a time when the North Sea should have been teeming with trawlers, drifters, submarines, and the odd patrolling warship, Möwe made her way across to the Pentland Firth and the channel leading to Scapa Flow unobserved, continuing west as far as Cape Wrath, quietly sowing a 250-300 mine field. The fact that Dohna-Schlodien and his crew accomplished this unchallenged over, by some accounts, multiple days, seems beyond belief. Perhaps the Royal Navy felt the tidal and seasonal weather conditions too difficult to contemplate such a possibility, yet it would cost them an eleven year-old battleship (HMS King Edward VII) and a few freighters, not to mention closing much of the strait to traffic for many months.

From these northern Scottish waters, Möwe proceeded out into the Atlantic, down the west coast of Ireland (although it wouldn’t have surprised me if Dohna-Schlodien had the stones to venture down through the Irish Sea) turning southeast toward the French coast. There she sowed her remaining mines, probably to the relief of her crew (mine laying, not to mention transport, is dangerous work). With the decks cleared, Dohna-Schlodien set a course south toward the shipping lanes along the West African coast.

On January 11, 1916, they encountered two merchantmen off the northwestern coast of Spain, a pair of British freighters. The first, SS Corbridge, was bound for Argentina with a load of coal. After a brief chase, she was taken intact as a prize and sent across the Atlantic to a point off the Brazilian coast and a future rendezvous for recoaling Möwe (Dohna-Schlodien was already planning a transatlantic crossing to the South American coast). SS Farringford, a freighter carrying a load of copper ore, was sunk by gunfire after her crew was taken off.

Two days later, January 13, another three British-flagged freighters were dispatched, one (SS Dromonby) being a westbound collier intended for recoaling British warships operating off South America. In three days they’d captured one ship and sunk four others, each without an alarm successfully raised by use of the victim’s wireless. Möwe, however, was getting a bit crowded accommodating the crews of four merchantmen, less the prize crew sent west aboard Corbridge.

(end of pt.1)

- simanton and Brooks Witten like this

#165

Posted 29 March 2021 - 04:40 PM

I always had the impression that commerce warfare wasn't a high priority for the KM because it wasn't "sexy" like lines of battleships slugging it out and conventional wisdom was that the war would be short and victorious with no need to resort to blockade/counter-blockade/commerce warfare. And there would have been budgetary priorities thrown in as well (German naval laws had a big bucket for battleships and another big bucket for cruisers, so of course Tirpitz spent the cruiser money on battlecruisers to boost his capital ship count...).

By the time January 1915 rolled around the war had lasted about 4-5 months longer than planned, with no sign of it ending any time soon and the RN slowly getting bigger relative to the HSF the Germans had to resort to Plan B. The initial submarine war and the use of AMCs all reeks of being ad hoc.

- simanton likes this

#166

Posted 29 March 2021 - 07:00 PM

I think the Kaiser had ideas the war would end "before the autumn leaves fall", but, from what I've read, many of his staff expected an eighteen month to two year timeline On the other side of the Channel, I seem to recall Kitchener, an acknowledged outlier, predicting a three-year blood-letting.

For the German Navy. the Kaiser was the wild card in the whole bloody mess. He maintained and exercised veto power over everything. I suspect a lot of what Tirpitz tried to do was lost in (1) the political game-playing by the Kaiser, Chancellor, and other high-ranking government officials, and (2) the accelerated breakout of hostilities that left much of the construction program "behind the curve". That said, I don't think Tirpitz and his staff were particularly good strategic "contingency" planners.

I would totally agree that commerce-raiding was the red-headed step-child in the KM's prewar strategic plan. It got little more than a nod from Tirpitz, and the U-boats eventually supplanted all of it. Maybe if the KM had been a bit more aggressive on a global basis leading up to the war, the RN would not have been able to recall nearly all of its heaviest units from the overseas stations in order to maintain a position of strength in the North Sea.

- simanton likes this

#167

Posted 29 March 2021 - 10:25 PM

Sadly, to me the HSF in the form it took was the result of Wilhelm II's vanity and jealousy toward Edward VII and Tirpitz' ambition. Again, sadly, it was a prime example of the German ability to take strategic absurdity to technical near-perfection. Sums of money expended on magnificent ships and men who could never make a significant difference in a war with Great Britain. The only way it could really have made a decisive difference would have been if it could have pulled of an invasion of Britain, which the Generalstab would never have provided the resources for.

#168

Posted 29 March 2021 - 10:28 PM

I always had the impression that commerce warfare wasn't a high priority for the KM because it wasn't "sexy" like lines of battleships slugging it out and conventional wisdom was that the war would be short and victorious with no need to resort to blockade/counter-blockade/commerce warfare. And there would have been budgetary priorities thrown in as well (German naval laws had a big bucket for battleships and another big bucket for cruisers, so of course Tirpitz spent the cruiser money on battlecruisers to boost his capital ship count...).

By the time January 1915 rolled around the war had lasted about 4-5 months longer than planned, with no sign of it ending any time soon and the RN slowly getting bigger relative to the HSF the Germans had to resort to Plan B. The initial submarine war and the use of AMCs all reeks of being ad hoc.

It absolutely was. As far as Britain was concerned, the German Navy was an illustration of Dr. Samuel Johnson's observation (not word for word, going from memory): "A horsefly, sir, can bite a noble steed and cause it to wince, but the one remains but an insect and the other is a horse still."

#169

Posted 31 March 2021 - 07:58 PM

Sadly, to me the HSF in the form it took was the result of Wilhelm II's vanity and jealousy toward Edward VII and Tirpitz' ambition. Again, sadly, it was a prime example of the German ability to take strategic absurdity to technical near-perfection. Sums of money expended on magnificent ships and men who could never make a significant difference in a war with Great Britain. The only way it could really have made a decisive difference would have been if it could have pulled of an invasion of Britain, which the Generalstab would never have provided the resources for.

Yes, reading Massie's book Dreadnought it struck me how much of the misery Germany caused itself and others in the 20th century comes down to a combination of ego, ambition, insecurity and sycophantry in the leading personalities of the Reich from the time of Bismark onwards.

Of course it could never possibly happen today, we have learned ever so much as a species ![]()

- simanton likes this

#170

Posted 31 March 2021 - 09:27 PM

Ya nailed it, Doug!

#171

Posted 02 April 2021 - 09:09 AM

I'm not sure that an invasion of Britain was ever contemplated, or even possible, during WWI. If so, it would have been far downstream in the eventual course of events. If the Germans were unprepared for such an endeavor in 1940, they were far less prepared in 1915-1916.

I do think some sort of a catastrophic defeat of the Royal Navy early on could have bent the curve significantly, but even that, given the personalities of the protagonists, seems highly unlikely. Beatty, the most reckless of the lot, nearly met his Armageddon on a number of occasions, but even if he and his beloved battlecruisers had been blotted out, I'm not sure that adds up to the level of loss required to move the needle in the Germans' favor.

I don't think the funds dedicated to the construction of the German navy was necessarily wasteful, I just think it was woefully misdirected. Had they dedicated the resources to building a global network capable of supporting world-wide operations, they could have "stretched the playing field" a bit. That, however, is hard to imagine happening. They didn't hold enough territories/colonies in strategic locations, and they don't have a good historical record of successfully negotiating treaties, except when they do so from a position of strength.

I tend to think of the British/German naval confrontation as a prize fight between a ham-fisted aging heavyweight and a young middleweight with a decent combination. The young guy will get in a few good licks, maybe stagger the old guy a bit, perhaps even knock him down, but in the end the youngster is going to get knocked onto the canvas. He doesn't have enough weight behind his punch to get it done.

And the Kaiser is his corner man...oy.

- simanton likes this

#172

Posted 02 April 2021 - 10:50 PM

That's just it! What other meaningful mission could have been the purpose of the Hochseeflotte? Control of the North Sea? Who cares? Britain can survive without it, it will never bring her to her knees! Hasn't been done since 1066 when William of Normandy brought an army over! Which was, as far as I am aware, NEVER a plan that the Heer bought into! "Woefully misdirected" indeed! Consider an alternative. A battle fleet designed with Russia as the foe. No British objection instead, if anything, encouragement! One less thing to worry about! For the rest, a cruiser navy on the high seas in alliance with Great Britain. HM Navy can NEVER have too many cruisers, a German navy voluntarily taking on part of the load is win-win for both sides. Alas, such a concept was beyond the imaginations of both Tirpitz and Wilhelm II. As Shakespeare's Puck observed: "Lord! What fools these mortals be!"

#173

Posted 03 April 2021 - 08:58 AM

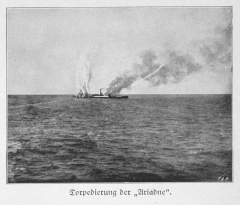

January 15, 1916

Early on the morning of January 15, Möwe stopped SS Ariadne off Madeira, a freighter bound for Nantes with a load of corn. After her crew was taken off, explosive charges were placed which, when detonated, failed to sink her. Defiantly remaining afloat, Dohna-Schlodien then ordered Ariadne sunk by gunfire, expending nearly a dozen 5.9-inch rounds. When this too failed, the freighter was sent to the bottom with the use of a torpedo.

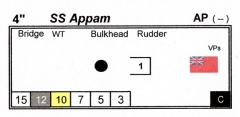

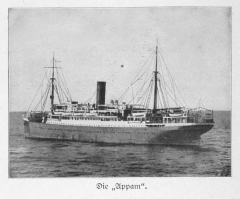

Around mid-day a new smudge of smoke appeared on the horizon, eventually identified as the northbound British passenger steamer SS Appam. Owned and operated by the British & African Steam Navigation Company, she was travelling from the Senegalese port of Dakar to Plymouth, England, carrying various cargo along with 168 passengers. Among them were a number of British dignitaries, along with thirteen enemy civilian prisoners and seven German POWs. She was commanded by Captain Henry G. Harrison. None of this, of course, was immediately known to the wary Dohna-Schlodien.

Assembling ship’s logs for Möwe and Appam was a bit of a challenge, as information is fairly sparse and what’s out there is often contradictory between sources. One of the biggest problems is finding reliable data for gross registered tonnage (GRT) and the ships’ engineering configuration and capabilities. I have a number of hard-copy sources here frequently referred to, and those, together with on-line sources/accounts, lead to a seemingly reasonable consensus view.

Möwe, as best I can tell, had a GRT of roughly 5000 tons and a top speed of 13-14 knots. She packed four hidden 5.9-inch and a single disguised 4.1-inch, along with a host of smaller weapons. Sources vary as to whether she carried two or four single-mount torpedo tubes; I opted to go with four. Originally built as a refrigerated freighter, she maintained some of that capability which, Dohna-Schlodien wrote in his 1916 account of the voyage, was useful for provision storage on the long voyage. Her coal bunkers had been enlarged in her conversion, which significantly expanded her potential operating range.

Appam is described by most sources as a passenger steamer of approximately 7800 GRT. I had trouble finding much in the way of a description of her engineering configuration or operating speed; however, Emmon’s book on the Atlantic liners gave single-screw vessels of similar size and configuration a speed of 13-16 knots, which I was able to loosely corroborate using Dunn’s Merchant Ships of the World, 1910-1929. At the time Appam encountered Möwe, she was slightly more than 1000 nautical miles out of Dakar, travelled over four days, which would put her cruising speed at roughly 11-12 knots. As far as whether she was armed or not, that too is open for debate, but a number of sources say she had a stern-mounted 4-inch gun and gunners trained to use it. I opted to include it.

Piecing together the exact chronology of Möwe’s encounter with Appam is a matter of slogging through various accounts to come up with a consensus view. Most hold few details, but we know Appam was churning north, likely at that 11-12 knot speed. According to Dohna-Schlodien’s book, he was growing increasingly leery of ships in the area, and ordered the “Red Duster” flying Möwe to cautiously close to within eight or nine nautical miles, then turn onto a parallel course where they were able to establish that it was not an enemy warship, but a medium-size passenger steamer. This did not, however, rule out the possibility of an AMC, at least one of which was known to be operating in the area (HMS Marmora, assigned to the Cape Verde Station). With no sign of a hostile reaction to their approach, Dohna-Schlodien ordered his helmsman to cross the ship’s bow a mile or so ahead, whereby they were able to identify her as SS Appam.

An illustration of the attack on SS Appam from The Illustrated London News of February 26, 1916, based on the recollections of a passenger aboard the cargo-liner. The drawing of Möwe's armament configuration is interesting, albeit flawed as compared to contemporary accounts.

Running up the German naval ensign in place of the British, Möwe flashed Appam two signals, the first to halt and the other to cease all radio transmissions. Henry Harrison complied with neither, ordering his ship to continue while the radioman frantically sent distress calls. Dohna-Schlodien ordered the partitions on his 5.9-inch dropped while slowly bringing Möwe around to fire a shot across the liner’s bow, all the while doing their best to jam Appam’s wireless transmissions (a capability I was unaware of). Harrison, having had a good look at his tormenter and reportedly concerned for the welfare of his passengers, ordered a full stop, whereupon she was boarded.

While the steamer didn’t dovetail well with Dohna-Schlodien’s profile for targets, the capture of Appam played fortuitously into his immediate needs. After offloading some valuable cargo, freeing the German prisoners, and detaining a number of the British on Möwe, he transferred the 200+ captured crew members of his recent victims to Appam. He then installed an armed prize crew led by Leutnant Hans Berg, supplemented by the seven German POWs already aboard. For the next two days, Möwe and Appam would operate together.

Game Prep

As I read accounts of this “action” 105 years after-the-fact, I find myself pondering the outcome and the behavior of the “players”. This is necessary, as part of the point of this exercise was to begin the development of some sort of “AI” to use for solitaire games of FAI. It’s fundamentally a determination of what’s technically possible and what the motivations are for certain decisions. To best do that, you have to look at what happened historically.

Back in the day, I did something similar for a few operational and tactical scale board wargames. For operational games, it boils down to identifying and establishing “decision points”. For example, if you’re playing an east-front game where the Germans are pushing east early in the war, you have to look at what the historical objectives were, and what the “flash-points” for decision-making might have been. If the Germans manage to establish a bridgehead on the eastern side of a major river, for instance, that is likely a point where the Soviets have to decide what they are going to do (given the time and resources available). They may decide to counterattack vigorously, they may decide to try to simply contain the Germans, they might decide to fall back to another defense line, or they may choose to do absolutely nothing. You weight each of those decision possibilities in light of things such as the tendencies of the historical commander(s), the units involved, supply considerations, maybe the weather, etc., build a table and roll dice when events occur. You can make it as complex as you want, as long as you keep within the bounds of what is reasonable and rational. In this way you can provide a bit of randomness in the behavior of your solitaire opponent. In many of today’s operational scale games, the introduction of random activation serves a similar purpose, although, IMHO, it seems to sharply increase the gaminess feel and occasionally leads to some fairly unrealistic results.

Tactical games such as FAI are a bit hairier. First off, the action is simultaneous, so there’s no I-go-you-go sequence of play to mess with. Decisions can be equally proactive and reactive, and they need to be framed by the circumstances. A careful review of the historical action will often provide the framework within which possible decision points can be identified. I have found that using a decision tree, while quite tedious, is very useful in mapping potential actions and weighting the decision possibilities that might present themselves. A variation of this was used during my working life when building complex one, three, and five year business plans, although there it was less about decision-making and more about just predicting financial outcomes.

In this case, it makes sense to play Möwe and let Appam be guided by the dice. Harrison’s objective is pretty straightforward – get his ship safely to Plymouth on time. His reaction to the possible threat posed by Dohna-Schlodien and Möwe, once identified, is the crux of the matter.

I freely admit to knowing very little about things such as the rules of navigation, i.e. who yields to who when ships encounter one another on the open sea. Certainly distraction, if allowed, can play into it, or worse yet, willful disregard. I know this from experience, having on more than one occasion nearly run a large sailboat aground while distracted by various goings-on, both aboard and nearby. Unlike me, Henry Harrison, as best I can tell, was a thoroughly experienced master, so I give him the benefit of the doubt.

In four days, a half-dozen British ships (including Ariadne that morning) had gone to vapor, yet shipping officials and the Royal Navy were apparently none the wiser. At first this might seem counterintuitive, but rolling the clock back a century, it becomes less so. Information flow between vessels and shore or other vessels, especially passenger ships, was routine, but minimal. Ocean-going ships were generally equipped with wireless equipment, but as seen on many occasions, the gear remained technically primitive, subject to problems in signal direction, strength, protocol, and/or inexperience by the operator (both sending and receiving). Failure to reach a ship by radio was indicative of a problem, but efforts to determine its fate, especially freighters, was often begun only after its failure to arrive at its destination by its scheduled call date. Reports of confirmed enemy sightings or attacks were routinely sent, but Appam had received none. In light of all of this, it’s not unreasonable that Harrison was unaware of the immediacy of the danger his ship was in.

Harrison, then, clearly had reason to be wary of the general, but not the immediate situation, on January 15. His voyage since leaving Dakar four days earlier had been uneventful. They’d received no reports of commerce raiders operating in the area. If anything, his concerns likely centered on the threat posed by submarines which were known to occasionally operate along the West African sea lanes. He was cruising at a speed that would get him into Plymouth on time and in the most fuel-efficient manner. Appam was not, however, zig-zagging or making any precautionary course or speed changes.

Historically, Harrison did almost nothing to save his ship, despite observing an admittedly rather generic British-flagged vessel operating in an erratic, if not threatening manner. It’s important to try to understand the rationale for his action (or inaction). He had options. Perhaps the welfare of his passengers, as he told Dohna-Schlodien, was his primary concern. Had there been published results from a contemporary board of inquiry (if one was held), those would have been quite useful.

As best I can tell, Möwe comes over the horizon on a southwesterly heading. At a distance of 9-10 nautical miles she makes an approximate 100+ degree turn onto a course that roughly parallels that of Appam. Travelling at a speed likely 2-3 knots faster than the passenger steamer, Möwe, flying the British red ensign, turns onto a northwesterly heading that will take her within a mile of Appam, eventually across her bow.

Through all of this, one is left to wonder what Harrison is thinking; perhaps even more importantly, one is left to wonder what Harrison could have done. By the time Möwe turns onto a course paralleling Appam, Dohna-Schlodien’s 5.9-inch battery is nearly within range. It seems to me, the critical and most rational decision point comes when Möwe turns to begin her run-in on Appam’s starboard bow. Harrison’s best chance for escape, perhaps only chance, is to abruptly turn away from the British-flagged tramp, go to flank speed, and man the 4-inch on her stern.

Models, charts, and dice in hand, we go to the table.

After Action Report

Based on the accounts provided by a few of Appam’s passengers, the weather on September 15 was near perfect. Sea conditions were “moderate” with a light chop. Visibility is clear all the way to the horizon in all directions. The air temperature is a balmy sixty degrees, water temp some ten to fifteen degrees cooler.

By mid-morning, Dohna-Schlodien has brought Ariadne’s crew aboard and dispatched the freighter by use of one of his precious torpedoes. His lower decks now crammed with prisoners, he orders Möwe off to resume a course to the southwest.

Around 1200, a lookout on Möwe reports smoke off the starboard bow, an unknown vessel on a due north heading. If they continue on their present course, Dohna-Schlodien determines that they will pass well astern of the ship. Wary of a rapid approach but hoping for a closer look, he maintains his heading for nearly thirty minutes, then orders the helmsman to bring Möwe around to a due north heading, roughly paralleling the other vessel. With the distance between them just ten miles, Dohna-Schlodien determines the ship to be a cargo-liner of some 8000 tons, but of unknown nationality. Keeping Möwe on her present course, he orders her speed increased to 13 knots, allowing them to slowly begin pulling ahead. Continuing for nearly an hour, he waits for some perceptible reaction by the other captain.

Aboard Appam, Captain Harrison is in the officers’ mess enjoying a lunch of salted kippers and brown bread, going over the morning fuel report with his engineering officer. At 1250, he is called to the bridge where he is told of the presence of an unidentified ship running on a parallel course, approximately ten miles off their starboard beam. When he asks how long the ship has been coming up from behind them, he is told that the ship actually approached from the northeast, then turned onto a course abreast their own. When he hears this, he berates the watch officer for not having called him to the bridge earlier. Through his binoculars, he sees a rather nondescript tramp pushing along at a speed slightly ahead of his own. Wondering why it made a rather sharp course change to mimic his own, he convinces himself that, while peculiar, it is not immediately concerning. He decides they will continue on their current heading and maintain their current speed (a d12 roll of 2 on our reaction table), while keeping an eye on the nearby ship.

At 1336, Dohna-Schlodien orders a course change to the northwest, which, if both ships continue their current headings and speed, will take Möwe across the liner’s bow at a distance of slightly more than a mile. Approaching a range of 14000 yards, he orders his gun crews to their hidden stations.

While the unidentified ship was still close to ten miles off and gradually pulling ahead of him, Harrison began to think that it might not pose a threat. Other than possibly a correction for a navigational error, he still had no explanation for its sudden course change, but as both ships continued on a parallel heading and the amount of water between them continued to grow, he was content to proceed while keeping an eye open. This temporary sense of disregard abruptly dissipated when the tramp started into a turn to port, taking a line that would cross Appam’s bow uncomfortably close. He ordered a signal sent, calling for the freighter to stand off, but there was no response. As the distance between the ships closes and thinking a collision possible, Harrison pondered momentarily whether to try to turn inside the tramp and pass him astern, or simply turn away and throw the stokers into high gear. Now beginning to suspect ill-intentions, he elected the latter and ordered a gradual 30-degree turn to port while telegraphing for flank speed (a pair of d12 rolls of 1 and 4 on our reaction table).

As the steamer started her great arcing turn to port, Dohna-Schlodien ordered Möwe to flank speed. The combination of his opponent’s hesitation, the ship’s turn, and Möwe’s increased speed has dropped the distance between them by another 3000 yards, now down to just 8600 yards. His radioman, monitoring transmissions from the liner, reports silence.

But now Dohna-Schlodien has a problem. The combination of turns and speed changes by both ships have left Möwe nearly dead astern of the liner, which is almost imperceptibly starting to pull away. Without a forward deck gun, he has no chance to take a shot at a target dead ahead; a shot will require a turn in either direction, bringing his 5.9-inch to bear. Such a turn will slow him considerably, allowing the liner to open the distance between them even faster.

Deciding he has little alternative, he orders a turn to starboard, the British ensign taken down and the German run up. A signal is sent announcing he is a German auxiliary cruiser and demanding the liner stop, which, in combination with a warning shot, Dohna-Schlodien hopes the Brit heeds. The partitions masking the 5.9-inch are lowered.

Harrison, studying his pursuer from astern, can’t observe much of what’s going on aboard the ship. He can, however, see that the “Red Duster” has been replaced with a different ensign, one he is unable to recognize from 4-1/2 miles away. Regardless, he knows this is further evidence of trouble, shortly confirmed by the message that his pursuer is a German warship together with a demand that he stop his ship. He disregards the message, directing instead that distress calls be sent. Maintaining his heading and speed, he orders all of the passengers to their cabins and his stern-mounted 4-inch manned and ready (a d12 roll of 12 on our reaction table). With the safety of his passengers and crew in mind, he directs the RN gun-crew that they are only to fire if fired upon.

While the radioman does his best to obliterate Appam’s distress calls, the 5.9-inch wait for Möwe’s turn to bring the liner into their arc. At 1440, Dohna-Schlodien gets his shot, but the turn has cost him over 1000 yards of range. At 9600 yards, they straddle the steamer, throwing up two towers of water on either side.

Minutes feel like hours as he tries to outrun his pursuer. Harrison sees the flash of the German’s guns just a moment before the splashes erupt next to Appam, one shell landing just forty feet off his stern, sending a cascade of water and a few splinters clattering along the sides of his ship. The next salvo, or possibly the one after, will likely auger into Appam with catastrophic effect. While he knows the range will lengthen if both ships continue on their present courses (which the German must if he is to continue firing), perhaps running his ship beyond effective range in a matter of 15-20 minutes, the risk of even a single hit is too great. While the Englishman yearns to continue the fight, he has to consider the welfare of his passengers. He orders the gun team to stand down and a message sent to his pursuer, “Stopping” (a d12 roll of 10 on the “continue or stop” reaction table).

(end of pt.2)

- simanton and Brooks Witten like this

#174

Posted 03 April 2021 - 11:19 PM

I have read accounts of The Battle of Coronel which state that von Spee's ships attempted to jam the British wireless. Going by memory, an account by the Glasgow cited the "howling" of the German Telefunken transmitters jamming signals heard by Glasgow's wireless operators.

#175

Posted 04 April 2021 - 07:31 AM

I have read accounts of The Battle of Coronel which state that von Spee's ships attempted to jam the British wireless. Going by memory, an account by the Glasgow cited the "howling" of the German Telefunken transmitters jamming signals heard by Glasgow's wireless operators.

I'd like to read more on this capability. I flipped a note to a couple of friends of mine who are USNA archivists, hoping they might have something. It would be interesting to understand how prevalent and effective it was.

Sometimes I feel like I've lived under a rock for 60 years...

- simanton likes this

#176

Posted 05 April 2021 - 01:08 PM

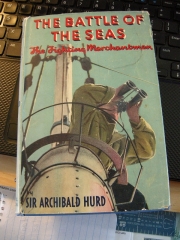

I found a nice used copy (1st edition) of Sir Archibald Hurd's "The Battle of the Seas", published in 1941:

Covering the plight of the British merchant ships during WWI and the early months of WWII, I recall reading this when I was a kid, borrowing it a number of times from our local library. I suspect this is a condensed version of his three-volume "The Merchant Navy", which I should run down copies of. I'm looking forward to rereading it.

- simanton likes this

#177

Posted 10 April 2021 - 08:53 AM

January 16, 1916

Clan Line Association Steamers was organized in Glasgow in the late 1800s by a consortium of Scottish investors, intended for service on the routes between Britain, South Africa, and India. Their timing was fortuitous, as Britain saw a boom in trade during the final decades of the nineteenth century, which led to the Clan Line’s rapid expansion. The company developed not only a reputation for expedient service, but also taking extraordinarily good care of cargoes, especially those which required special handling. One such cargo was tea, which had to be carefully segregated from other hold contents to avoid contamination. The Clan Line would dominate the highly-profitable tea trade for decades, its near monopolistic grip not broken until the years immediately following the Second World War.

During the first decade of the new century, trade fell into a bit of decline, while the competition for cargo grew. Shippers called upon the Clan Line to add Australia and New Zealand to its routes. At first the cargoes carried were largely dry goods such as wool, flax, and other nonperishables, but eventually a market for mutton, beef, and dairy began to develop, requiring the use of refrigerated ships. Charles Cayzer, a founder and the managing partner of the line, was reluctant to branch out into refrigeration, but he was eventually convinced by younger managers in the company. It proved a good decision, as refrigerated cargo handling would become a key component of the line’s business, especially during the economically difficult interwar years.

The line operated more than 80 ships over the course of the First World War, 28 of which were lost (fully a third of the line’s fleet). That’s a pretty horrendous rate of loss, but generally indicative of not only what was happening on the sea lanes for the first three years of the war, but also the company’s continued dedication to its lucrative, increasingly risky routes. The company lost not only many ships, but hundreds of employees as well during the fight on the high seas (not to mention those that went into the army and became casualties on the Western Front).

A number of the Clan Line’s ships were taken by the German surface raiders, the first being Calcutta-bound Clan Matheson, a general cargo freighter sunk in the Bay of Bengal by the Emden on September 14, 1914. A month later, the company lost another Calcutta-bound freighter, Clan Grant, also sunk by Emden a bit further west. The next would come some 15 months later.

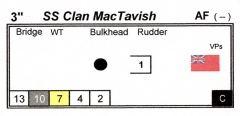

Clan MacTavish, a relatively recent addition to the line, was a 5816 GRT refrigerated cargo ship launched in 1912 from the Armstrong-Whitworth yards at Newcastle. Hers was a record of highly-profitable voyages between Britain and the ports of South Asia and the southwestern Pacific. On December 9, 1915, she found herself casting off at Wellington, New Zealand, bound for London with a cargo comprised of wool, mutton, leather, tinned meats and grain. She was captained by a tough Scotsman, William N. Oliver. Her voyage across the Indian Ocean was uneventful and, after a brief stop at Durban, South Africa, she set off for Dakar where she would coal and have a six-pounder quick-firing naval gun, likely a Hotchkiss, mounted on her stern. Many historians deride the Hotchkiss as a largely ineffective weapon, but it was intended as defense against light torpedo boats and submarines, not a heavily armed warship. With two Royal Navy gunners aboard to crew the six-pounder, she set off from Dakar on January 13, 1916.

By mid-day on the 16th, Dohna-Schlodien had spent the better part of 24 hours retrieving various bits of cargo off the Appam (including some £30,000 of gold bullion), while transferring more than two hundred prisoners held on Möwe to the cargo liner. He planned to keep the steamer handy for a few days, then send it off to be interned in the U. S. or South America. In the meantime, Leutnant Hans Berg and the prize crew had taken a firm grip on Appam’s operations, assuring the ship’s complement and passengers that she would be scuttled if their cooperation was not forthcoming and maintained.

Game Prep

I did a bit of rework on the reaction/decision tables, as the play from the 15th felt entirely too scripted for my liking. I realize now that I’d skewed the tables toward outcomes I’d thought likely, rather than outcomes that were merely possible. After expanding the decision tree and the list of “events” that call for reactions, I think I have a better list of outcomes to balance against.

That said, a bit of tailoring was still required. The notional restraints on Harrison (Appam) are quite different from those on Oliver (Clan MacTavish), at least from the standpoint of Oliver not having to concern himself with the welfare of 140+ civilian passengers. He could be a bit more reckless in his decision-making, and I needed to reflect that here.

Assembling a ship’s log for Clan MacTavish was relatively straightforward. There are a number of sources providing GRT, speed, and other basic engineering attributes, all providing the same basic data. What was less definitive was her armament, or more precisely, where the six-pounder was mounted. Most sources simply refer to a “stern-mount” for the gun, but Bernard Edwards specified that the gun “was so mounted on the Clan MacTavish’s port quarter that it gave no cover to the starboard side.” No other source mentioned this, and Edwards provided no cite, so it’s difficult to corroborate. While I have no reason to doubt Edwards’ account, it seems illogical to me, so I went with a wide-ranging stern mount.

Oliver’s ship is tracking north and, quite late in the afternoon, two ships (unbeknownst to him, Möwe and Appam) appear on his port bow, some eight or nine miles off, crossing ahead. We’ll make the presumption that Clan MacTavish, Möwe, and Appam are all proceeding at 10 knots. Weather is clear, seas are gentle. Oliver holds his course, presuming these ships pose no threat to Clan MacTavish while knowing his is the “stand on ship” by the rules of navigation. The two ships, approaching from the west, continue their seeming reckless approach.

After Action Report

Having sighted an approaching freighter on his starboard bow and wishing to investigate, Dohna-Schlodien orders Appam away to the northeast to stand off at some 20-30 miles. Noting the fading sunlight, a glance at his watch reveals it is 1724. The sun will set around 1830, which doesn’t leave much time to reach the freighter in daylight. Estimating the ship’s speed to be roughly the same as Möwe, he calculates they will pass quite close in fifty minutes, but only if both maintain their current speed and headings.

William Oliver suffers no fools, especially himself. He’s an eternal skeptic in the behavior of others, and the two ships he’s been observing off his port bow appear to be intent on crossing ahead at a distance too close for comfort. They don’t appear to be of any real threat to his ship, other than their obtuse navigation. Presuming these are two steamers bound for Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, he takes some comfort when the lead ship changes course to a northeastern heading, but notes that the second ship, lagging the first by nearly a mile, continues due east. At 1736, convinced there’s no accounting for such idiocy, he orders Clan MacTavish to turn thirty degrees to port onto a north-northwest heading that will allow her to pass well astern of the miscreant (a d12 roll of 5 on the reaction table)

As the distance between the ships rapidly decreases, Dohna-Schlodien gets a good look at the freighter. He can see that she’s quite a bit bigger than Möwe, perhaps some twenty percent in GRT, and British-flagged. Continuing on his current heading, he crosses some five-and-one-half miles ahead of her at 1754. Hoping not to alarm his quarry, he has Möwe slow to eight knots and start a gradual turn to the north-northeast.

Due south and just three-and-one-half miles dead astern of the tramp steamer, the ever-cautious master of Clan MacTavish eyes the ship with suspicion. Maintaining his course, he messages by lamp “What ship is that?”, then a minute later, “Do you require assistance?”. With neither query answered, Oliver makes the presumption that the ship is up to something and, at 1818, orders his gun manned, a turn to the northwest, all ahead flank (a d12 roll of 1 on the reaction table for “get the hell out of here”, a d12 roll of 10 for directional course change, and a d12 roll of 11 for speed change).

Dohna-Schlodien watches the freighter heel slightly as she makes a turn further west and accelerates. With the range widened to slightly more than four miles, and once again having gotten himself dead ahead of the British ship, he realizes there’s no point in continuing the charade. He orders a “Stop at once” message sent, has the Red Duster run down, replaced by the German naval ensign. He tells the helmsman to start a turn to the northwest and orders all ahead full as the gun crews drop the canvas partitions.

Oliver ignores the German’s stop order, instead directing his radioman to send repeated distress messages. He tells the engineering officer to have his Lascar firemen shovel like their very lives depend upon it (which they likely do), and gives his RN gun crew permission to fire when ready. The two ships are now running near parallel courses northwest, slightly less than four miles apart. Both captains know that there’s maybe 20 minutes of rapidly failing light, then covering darkness.

At 1842, Möwe gives a warning shot across the bow with its stern-mounted 4.1-inch. Standing on the starboard side of the bridge, Oliver ignores the warning shot, grinning slightly when hears the 6-pounder bark in response. A small splash appears well short of the German.

With no indication the freighter intends to stop, Dohna-Schlodien opens with his 5.9-inch at 1848, missing just short of the freighter midship. He orders Möwe a further turn west-northwest, attempting to close the range, while Oliver maintains his course and every stitch of speed he could wring from MacTavish’s plant. The range grows to a bit less than 7600 yards.

Möwe’s 5.9-inch and stern guns continue firing, scoring no hits on the great lumbering freighter. At 1900, Oliver orders cease-fire so that the 6-pounder’s muzzle flash won’t betray their position in the deepening darkness. With all lights extinguished and course maintained, he orders a speed reduction to 10 knots, staunching the position-revealing plume of embers pouring out of her funnel at flank speed.

As the British freighter disappears into the darkness, Dohna-Schlodien also orders his guns to cease firing. With precious little moonlight, the last reported range was down to a bit less than 6200 yards. He reduces speed to 11 knots, similarly mitigating Möwe’s funnel glow and wake on the mirror-like surface.

At 1918, Oliver orders MacTavish slowed to just five knots, hopeful that his antagonist will continue at breakneck speed, overshoot his location and pass into the night. Within minutes, however, his luck briefly turns. A lookout on Möwe spots the dark mass of the freighter just 4800 yards off their port beam, and Dohna-Schlodien orders fire resumed.

Seeing the muzzle-flashes on his starboard bow, Oliver orders MacTavish’s speed back to flank and turns into the German raider. Head on, his silhouette is narrowed significantly, but that’s a secondary consideration. Worst case, he’ll ram the German, full speed, ending this now. Looking up at the ship’s clock, it’s 1942.

The range is drawing down to point-blank. The German 5.9-inch maintain their fire, but score no hits. They can clearly see the oncoming freighter now, scarcely a mile-and-a-half away, a great frothy bow wave boiling up in front of her. At 1948, Dohna-Schlodien flips on his searchlights, now realizing the Brit’s grim intent. He orders flank speed in an effort to escape. At 1950, Oliver abruptly orders MacTavish to turn inside Möwe’s stern, passing within just 1200 yards.

Once clear of the German, Oliver again orders speed reduced to 10 knots, the two ships now rapidly moving away from each other. As the range grows, Möwe’s 4.1-inch swings around and fires a final time, missing badly. Clan MacTavish, not a nick on her, slips back into the darkness.

(end of pt.3)

- simanton and Brooks Witten like this

#178

Posted 12 April 2021 - 11:50 AM

The real story of Clan MacTavish, of course, ended rather badly, with most accounts raising more questions than they answer. Oliver, the conservative and cautious Scot, seemed to take few precautions and allowed Dohna-Schlodien to lull him into a state of near complacency. It cost him his ship and two dozen dead and wounded. The notion that historical hindsight is always 20-20 is a valid one, yet I find myself continuing to wonder how these ships’ masters allowed themselves to be taken in and down so easily.

One might start the rationalization process by acknowledging that Möwe was the first of her breed, an armed auxiliary cruiser disguised as a tramp steamer, and only recently entering service. When she encountered MacTavish, it had only been five days since she’d claimed her first victims, likely insufficient time for the alarm to have been raised of a piratical German raider operating in the West African shipping lanes.

Still, there were, and are, rules of navigation to be abided, and when a ship, clearly on a course other than your own, alters course in order to run parallel, that would seem indicative of some “peculiar” intent. Merchant ships have places to be, often with lucrative incentives for the captain to make schedule; they don’t typically sail haphazardly in a circuitous fashion. Yet, time and again, this is precisely what happened. In MacTavish’s case, Oliver, after exchanging requests for identification, ultimately allowed Möwe to close to within just 300 yards, whereupon she dropped her disguise and demanded his full stop. Only then did the Scotsman realize the game was indeed afoot and decide to attempt an ill-fated run for it.

It’s easy, 105 years later, to question someone’s ability to assess risk, but it seems in weighing the odds between making schedule or losing one’s ship, the decision for the former outweighed the latter. That, at least, is my take on it.

The other question that comes up is just how effective is the German 5.9-inch at the outer bands of its range. At 6000 yards, firing over open sights, the 5.9-inch has a one-in-four chance of scoring a hit. In my replay, Möwe opened on Clan MacTavish at around four miles (a bit beyond 7000 yards, a one-in-six probability), scoring no hits, and this continued even as the range closed. I freely admit to being one of the poorest die-rollers of all time, but it soon became apparent that the weight of two 5.9-inch tubes (one d12 roll per salvo) at a reasonable distance was a stretch for favorable results. That said, just one or two hits were likely sufficient to cripple the target.

So this exercise has answered little. My random-behavioral tables, supplemented with a few die-rolls to address minor issues along the way, seemed to work, fortunately not yielding anything too crazy (well maybe a decision to charge/ram was outside the norm). It will be interesting to try them with a few more ships on the table. Before that, however, there’s one final bit of this Möwe saga to explore.

And BTW, there’s a pair of relatively new d12 dice laying somewhere out in my backyard. You’re welcome to come retrieve them, but in my experience, they’re not worth it.

- simanton and Brooks Witten like this

#179

Posted 13 April 2021 - 04:51 PM

Just thinking that the whole idea of being a commerce raiding victim must have been the last thing on Oliver's mind. There really hadn't been a major commerce war in European waters for decades before 1914... maybe as far back as 1814. So the idea that you're going to be a victim just would not register. Very different in '39 when commerce war and blockade/counter-blockade were fresh in living memory. A modern analogy that comes to mind is driving the same route to work every day for years and not really noticing the beggar coming to ask for change who turns out to be a car-jacker... it is something you heard about on the news but never near where you live let alone to someone you know.

- simanton likes this

#180

Posted 16 April 2021 - 08:23 AM

I would agree, as it seems the only logical explanation. The fact that there were, at the time, no reported instances of a ship being confronted by a disguised merchantman lends credence to the concept, although Oliver, in his discussions with Dohna-Schlodien (as disclosed by the German) after being brought on-board Möwe, said he'd held considerable suspicions in the early stage of the encounter. I know in my own professional life of some 40 years it was sometimes easy to look past possibilities, or simply make a poor assessment of risk. It's human nature, I suppose. You hope for the best, but prepare for the worst, something that's not always optimal. Oliver paid a heavy price, as my understanding is he and his Royal Navy gun crew were retained on Möwe as prisoners, while the surviving members of the crew were transferred to Appam and sent off for internment. Oliver spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp.

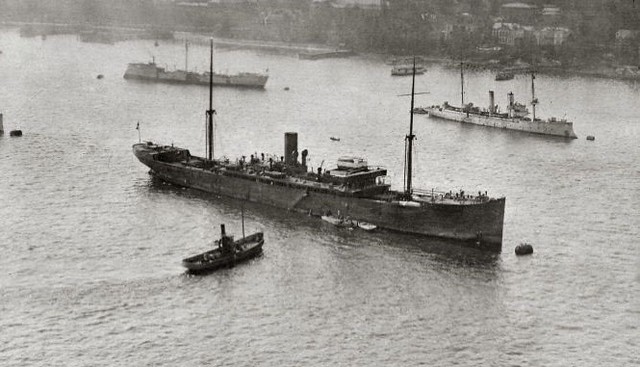

And then there's the "second battle" for the Appam, this one ultimately fought in the U. S. Supreme Court following its bid for internment at Newport News. While there were already a number of German ships interned in the U. S., Appam's case was unusual/different as she was a prize of war. Upon her arrival in the U. S., the British consulate immediately pressed for the ship's return to her rightful owners. The case would eventually find it's way up to the Supreme Court, with a ruling in the Brits' favor.

SS Appam's 1916 arrival at Newport News, Virginia, in her bid for internship in the still-neutral United States (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

SS Appam's 1916 arrival at Newport News, Virginia, in her bid for internship in the still-neutral United States (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Here's an interesting article that does a decent job of recapping the case and the central arguments of the German and British consulates:

https://academic.oup...9/2/477/5057080

- simanton likes this

Also tagged with one or more of these keywords: FAI

Fleet Action Imminent Forum →

Comments, Discussions & General Q&A →

Firing on small craft FAIStarted by Swagman1982 , 14 Feb 2019 |

|

|

||

Fleet Action Imminent Forum →

Comments, Discussions & General Q&A →

Swedish Navy WW1Started by Mel Spence , 23 Sep 2015 |

|

|

1 user(s) are reading this topic

0 members, 1 guests, 0 anonymous users