Recent Musings

AARs are scarce, I’m afraid, as there’s been precious little action around here. Wariness of gatherings remains abundant these days, for good reason. I’m in the same camp, so instead I’ve rededicated myself to hewing away on the unpainted lead/resin pile while doing a bit of research.

Reading up on WWI U-boat action led me to a revisit of the British innovation of the Q-ship, which then morphed into a detailed look at the armed merchant cruiser or auxiliary cruiser, depending upon whose navy you were reading about. The Q-ship was definitely a response to the relatively new phenomena of the submarine(s), but the AMC or auxiliary cruiser was a modernization of a tactic used for centuries. Both were largely built around the premise of pretending to being something or someone you weren’t, either by altering one’s appearance, or flying the flag and markings of a friendly or nonbelligerent. These tactics, the ships, and the men that commanded/manned them, are very interesting.

One problem is running down accurate descriptions of the ships themselves. Many sources have entries, but there are a lot of discrepancies between them. This may be the result of the ships being reconfigured a number of times over the course of their existence, the repair of damage, but likely just the paucity of credible information due to the circumstances of their operation.

Most data on the Q-ships is anecdotal, found in bits in various accounts of engagements. I have yet to find a comprehensive list of them, their size, configuration, or operational capabilities. The best you can usually do is tonnage, crew size, and basic armament (although not necessarily how or where it was mounted). With that information, together with a photo if one can be found, a presumptive FAI ship’s log can be cobbled together. Other intangibles add to the difficulty. For instance, it was not uncommon for the holds of a Q to be loaded with lumber, hundreds of empty capped oil drums, and other materials aimed to increase buoyancy when damaged. There are numerous accounts of ships taking multiple torpedo hits, raked by gunfire, yet still able to fight on, sometimes for hours before eventually succumbing. Some also had rudimentary armor fashioned from sandbags and other materials, especially around the bridge and various communications and engineering areas. I start with the merchant ship hull box chart and build from there.

Info on the armed merchant cruisers and auxiliary cruisers seems somewhat easier to find, possibly because there were so few of them. This may also be true because they were operated more tightly as true warships of the respective navies. Still, basic data can vary sharply between sources. While little may tie out exactly, reviewing three or four credible sources which aren’t simply printing what the other guy said, and you can begin to corroborate and assemble a general sense of a ship’s configuration. The number, position, and configuration of torpedo-tube mounts can be especially challenging.

So, a few ships have travelled across the workbench of late. First up, as noted in a previous post, came a look at SMS Möwe, an auxiliary cruiser of the Kaiser’s navy. Möwe had an extraordinarily successful record during the war, sinking some forty ships, including the mining of an old predreadnought battleship. Although she was rather substantially damaged in at least two engagements, she survived the war. As best I can tell, she was armed with four 5.9-inch in single mounts (hidden behind false hull panels) with a 4.1-inch mount on her bow. She had at least a pair of 20-inch torpedo tubes. She also carried a substantial number of mines. She displaced roughly 9800 tons, was roughly 400 feet long, with three coal-fueled triple-expansion engines. Most sources list her top speed at 13 knots, but accounts indicate she had occasionally run down quarry at speeds approaching 15-16 knots.

If source material is reasonably accurate, the Panzerschiffe model I have of Möwe has some inaccuracies (even the basic profile appears to be inaccurate). Finding her paint scheme is difficult, sources varying widely. Most show her to have had a beige-colored deck. This would imply that her deck was sheathed in wood, which seems unlikely but not impossible. I settled on a dark hull, white uppers, and a black funnel, aligning with a couple of the photos I’ve seen of her.

SMS Möwe

Another ship that caught my eye was HK Komet, an auxiliary cruiser operated by the Kriegsmarine during WWII. Hers was a relatively short career, operating successfully in the South Pacific in 1940/1941, where she had a hand in sinking or capturing eight ships. She was sunk by a British MTB at the start of her second cruise, October of 1942, attempting to run the blockade and pass through the English Channel on her way to the Atlantic. Built in 1937 as a freighter, displacement of 7500 tons, propelled by a pair of 6-cylinder diesels giving her a top-speed of 16 knots. She was armed with six 5.9-inch single mounts, a 60mm on her bow, four 20mm AA, and a twin 37mm AA mount on her stern. Her torpedo armament is described as six 21-inch tubes in two two-tube mounts and two submerged single tubes. Interestingly, she also carried a pair of Arado float-planes for recon purposes, stored in her forward hold and launched, as best I can tell, by catapult.

Photos of Komet are scarce, but one I have seen indicates a dark gray color for her hull, with dark uppers and funnel. No idea what her deck looked like, but I’ll presume steel painted a haze gray. Another Panzerschiffe model, my Komet looks to be fairly accurate in configuration, with the gun position placement to be approximate. I toyed with adding a catapult and a GHQ Arado float-plane, but got lazy and didn’t. Consider them stowed.

HK Komet

The auxiliary cruisers typically tried to disguise themselves as ordinary merchantmen, flying other national ensigns, painting in markings other than their own, and often giving their uppers the colors of the various shipping companies. Funnel markings were routinely mimicked. The fact that ships maintained their owners’ funnel bands throughout the war surprised me, as I would have thought all of that would have been blotted out in some sort of overall gray paint scheme. Some merchantmen did adopt national schemes, even dazzle schemes were deployed, in the last years of the war (here's an interesting link to a discussion on the NARA site, re: dazzle camo as employed on merchant ships: https://unwritten-re...lates-from-wwi/ )

Which then brings up the question of what the typical merchantman actually looked like. As best I can tell, it was quite a mish-mash early on, with the shipping companies slow to adopt the recommended drab gray paint schemes. By the time the convoy system/routes were developed and implemented, much of the individuality of ship markings, other than the funnels bands, had been painted over (although their outlines remained fundamentally the same). Steel decks had their linoleum stripped (if they had it), repainted with anti-skid paint (paint with a fistful of sand or grit added) in whatever color was handy.

During WWI, colliers were mission critical to all of the navies, especially those still operating coal-fueled warships in areas where friendly ports were scarce. The British maintained an extensive replenishment operation known as the Royal Fleet Auxiliary, which was supplemented through the use of chartered auxiliaries drawn from the private shipping companies (the RFA continued through WWII and much of the postwar era as well). As the WWI navies displaced coal with oil as their primary fuel, many of the colliers were converted to tankers.

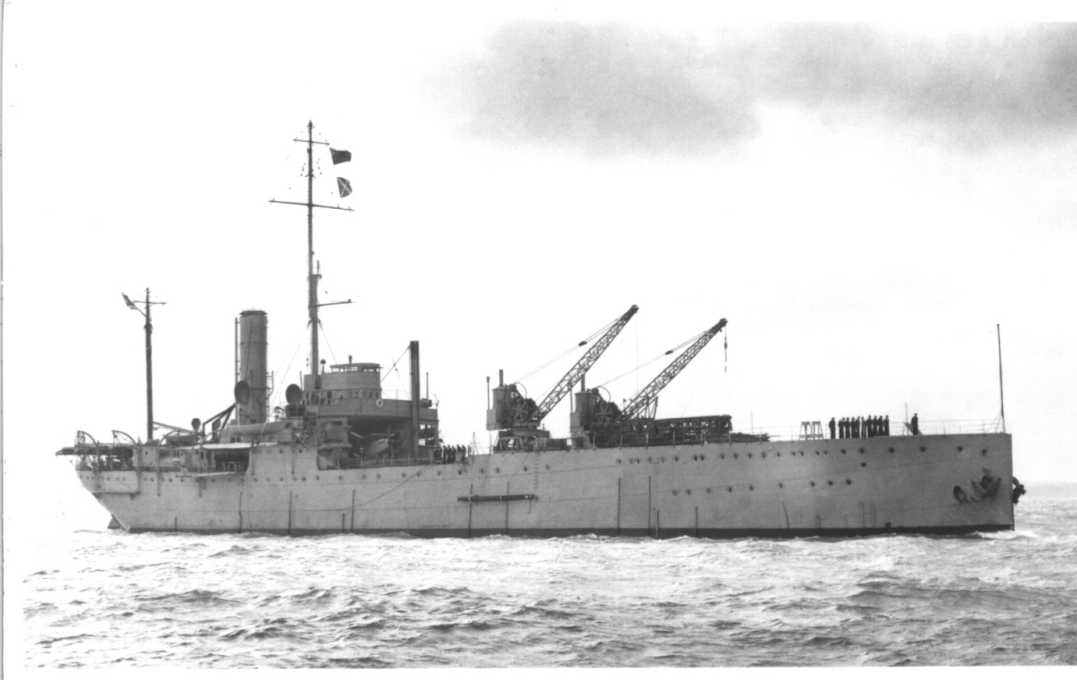

RFA Mercedes

RFA Mercedes

Interestingly, I believe the RFA rostered and operated only a single collier during WWI, the Mercedes. As best I can tell, the many others that the RN/RFA employed were all requisitioned and chartered. With that in mind, you can well imagine the diverse fleet of ships pressed into service as colliers, many never having hauled any coal previously. Panzerschiffe offers a model of the Mercedes, calling it a “typical collier”. It was, in fact, anything but typical. Mercedes, a one-off, built with her bridge and control functions mid-ship and all of her engineering and propulsion gear at the stern (most cargo ships of the day had control and engineering functions amidships).

Unfortunately, I had two of Panzerschiffe’s British collier model in inventory, so I took some liberties in making a second of the Mercedes “class”. In this way, SS Aberfan was commissioned, named after a town in the coal-rich southwest corner of Wales.

SS Aberfan

May God bless her and all who sail in her.

(to be continued)